Student Exhibits

Students employed in the Anthropology Lab at Luther College have the opportunity to develop, design, and implement exhibits for several of the anthropology sponsored display cases across campus. Exhibits often feature objects from the Anthropology Lab collections and focused research on themes relating to anthropology, archaeology, material culture, history, art history, and other student selected topics.

Lab, Displays, and Exhibits

Preus Library: Main Floor

The Mystery of the Beaded Bags in the Anthropology Collection

By Alison Gau (’18)

Bandolier bags or gashkibidaaganag are large, beaded bags that are worn across the shoulder as demonstrated by Young Beaver in Figure 1. These bags are beautiful creations that are culturally significant to the Algonquian-speaking Native American tribes of the Great Lakes area, especially the Ojibwe tribe. Each of the four bags on display is unique in that each design is a reflection of the bead artists’ creativity and skill. The artists, mainly women, would draw inspiration from the environment around them and incorporate their interpretations of natural motifs into their bead work design. The designs were also influenced through interactions with other Native American tribes and Euro-American people.

Koren

Let’s Get Geophysical First Floor

By Morgan Niner (’20)

Learn about the latest geophysical technology employed by Luther College Anthropology in its archaeology research under the direction of Colin Betts.

Liberty in History Second Floor

By Meta Miller, museum studies minor (’21)

This exhibit draws on the Anthropology Numismatics Collection to highlight the past and current trends in depicting Lady Liberty on American currency.

Who’s Who in Luther Anthropology Third Floor

Check out the current faculty and students in the Anthropology program. See the various accomplishments of members of our department.

Olin First Floor

Souvenirs of Colonial India

By Froeydis Roenneberg (’18)

See over 75 historic clay figurines constructed in the last decade of the 1800s and learn the story of how Luther College came to have this remarkable collection and steps to stabilize and conserve them as part of museum conservation practice.

Larsen Center for Global Learning

Beads of Change: Maasai Women’s Role in the Market

By Abby Vidmar (’19)

Stop by the Center for Global Learning to check out the display based on Abby’s semester of study abroad.

Mallam’s Legacy: The Luther College Anthropology Lab

The LCARC was founded by R. Clark Mallam in the fall of 1969 with the acquisition of several thousand Native American artifacts donated by Gavin Sampson. To professionally organize the influx of new items, Mallam turned to the Smithsonian for assistance. George Metcalf, their Chief of the Processing Laboratory, came as a consultant for two weeks, after which the LCARC was fully functional. With the addition of a field school and more donations, LCARC became the “largest [archaeological] research program in Iowa” at the time (Status Report, 1983: 1).

The job titles and duties have changed over time, but LCARC has always had a director. In order to accommodate NAGPRA and supervise student workers, a lab technician or collections manager was added to the staff in the early 1990s.

Student workers process a soil sample from Luther’s archaeology field school by using the flotation method which dissolves soil to recover seeds and other micro-sized objects which may be contained within the soil.

According to Mallam’s status reports, the original goal of LCARC was “to use archaeology as an instrument for promoting the anthropological perspective–the study and appreciation of other cultural adaptations and beliefs – within the context of the liberal arts.” This was accomplished by training and teaching students how to conduct research, excavate sites, and complete archeological conservation projects led by Luther’s anthropology staff.

The completion of contract work, the process of excavating archaeological sites, and researching for the Iowa Office of the State Archaeologist were special aspects of LCARC from 1970-1987. Through the meaningful contributions of students and faculty, the LCARC was able to complete over 50 projects resulting in 32 published reports. At the time, only large universities had the resources to pursue archaeological contracts, so it was impressive that Luther was able to give undergraduate students a chance to participate in this work.

At the time of its creation, LCARC and its collections were located in the stacks area of the old Koren Library-four floors of workspace and storage. When Koren was renovated in 1987, the collections were moved to their current location, a 1250 square foot climate-controlled storage facility in the basement of Preus Library. The workspace, now known as the Anthropology Lab, resides on the third floor of Koren. It comprises several computer workstations, scanners, cameras, transcription machines, GPS equipment, a 3D scanner, the teaching collection, and a wide range of relevant books and reports.

The Anthropology Lab is supported through the contributions of its student workers. The Lab employs an average of thirteen students per semester, most of whom are anthropology majors, but also students who study history, museum studies, and classics. Workers update databases and practice techniques for collections management, exhibit creation, and archaeological data analysis.

Some specific examples of student projects include: digitization and transcription of ethnographic interviews for the Chiwere Language Project, designing exhibits across the Luther campus, and writing archaeological reports based on LCARC excavations, like Drahn Farm. They have also been processing new acquisitions into the collections, digitizing paper-based collection records, transferring the old database and object records to a new online collections database, and inventorying and photographing the anthropology collections.

Currently, the Anthropology Lab curates three distinct collections: the Archaeological Collection, the Ethnographic Collection, and the Numismatic Collection.

For the last two decades, students have used the Anthropology Collections to hone their research skills and supply objects for student exhibits. Luther’s anthropology program uses its collections as teaching tools in classes and to provide learning experiences outside the classroom. The collections are also available to outside researchers. In addition, Luther’s archaeology field school utilizes the lab’s resources for analysis before adding artifacts to the Archaeological Collection.

In the 2012-2013 school year, our Koren display cases featured the story of the lab’s history, its founder, Dr. R. Clark Mallam, and its work. Exhibit creators were Dan Hess (’13), Kirk Lehmann (’13), Cassie Kubicek (’13), and Lisa Stippich (’14).

Dr. Richard “Clark” Mallam (1940-1986) was the founder of Luther College’s anthropology program (1969). Here we celebrate and highlight the many contributions and connections made by this beloved professor.

Journey from Education to Educator

Mallam’s educational experiences taught him to critically assess what others had said about the Native American cultures he studied. Because the American educational system exposed him to “distortion, inaccuracy, and misrepresentation” regarding these groups, he felt the desire to rectify these problems by educating others.

In 1969, Clark accepted a position at Luther College where he founded and expanded the new anthropology program. He created the Luther College Archaeological Research Center (LCARC), which soon housed the largest collection of northeastern Iowa Native American artifacts at the time, and he began to direct and teach anthropology classes. In these, he encouraged students to closely analyze their sources, evaluate evidence, and to draw their own conclusions.

Educational Profile

- Associate of Arts degree, Fairbury Junior College, Nebraska (1959)

- Field Infantry Medic, Alaskan Command, (1959-1961)

- B.S. in History, University of Nebraska (1963)

- M.A. in Anthropology, Adams State College (1966)

- M.Ph. in American Indian Education, University of Kansas (1973)

- Ph.D. in American Indian Education, University of Kansas (1975)

Capoli Bluff Mound Group, image courtesy of Lori Stanley

The Effigy Mounds are large earthworks constructed in the shapes of various animal or human forms. There are also other types of mounds such as conical and linear, which can be found in various other regions. However, the effigy form is a phenomenon restricted to the “Driftless Area” of the Midwest, which encompasses northern Illinois, southern Wisconsin, and eastern Iowa. This area is so named as it escaped the glaciations of the Pleistocene Epoch (2,588,000 to 11,700 years ago) giving it a distinct topography from the surrounding land.

The Inhabitants

The first burial mounds in the United States were conical, built in Wisconsin during the Late Archaic period (5,000 – 3,000 years ago). The oldest evidence of inhabitants in the Driftless Area are Folsom and Clovis projectile points which date back to well over 10,000 years old. However, the inhabitants exclusively associated with the construction of the effigy mounds are from the Late Woodland Period (1400 – 750 years ago). These people were hunter-gatherers who used stone, bone, and antler tools to exploit the rivers and forests of the area. After this period all effigy-shaped mound building ceased, yet conical and linear construction continued on a reduced scale until approximately the 16th century.

The Mound Builder Myth

The Mound Builder Myth was a popular 19th century belief that there was a master race of prehistoric builders who preceded the Native Americans. People of this century largely held the bias that the Native Americans lacked the technological expertise or mental capacity to create such complex structures. Therefore, there must have been a prehistoric people distinct from the ancestors of the Native Americans. Due to this bias, the early research of the effigy mounds was devoted to a larger investigation of this myth, and there was a great amount of ease to which “discovery” was integrated into this idea. The common belief at the time was that the mounds served a sacrificial purpose or as fortifications.

The Hill-Lewis Survey and Ellison Orr

In 1880, the Northern Archaeological Survey was conducted by Alfred James Hill and Theodore Hayes Lewis. Conducting the majority of the fieldwork himself, Lewis traveled for 15 years throughout the Midwest. By the end of the survey he had compiled 40 field notebooks and surveyed 13,000 mounds.

Approximately 50 years later, from 1934 through 1936, Ellison Orr conducted the Iowa Archaeological Survey. During the time of his fieldwork he excavated various conical and linear mounds, along with one effigy mound. In the end, he concluded that “[t]he effigy mounds of Iowa are apparently an overrun from Wisconsin, in the southern part of the state of which they are very abundant,” so from that point forward, effigy mound research was focused solely within the state of Wisconsin.

Both of these early surveys were incomplete, and since then many mounds were destroyed due to expanding agricultural efforts. However, through Orr’s efforts, the effigy mounds were declared a national monument in 1949, largely due to the iconic “marching bears” mound group.

The Transition in Archaeological Ideology

During the time of Clark Mallam’s research, there was the beginning of a transition from a culture-historical approach to a processual approach in archaeology. Previous research on the effigy mounds had focused on describing, recording, or establishing culture-historical sequences with regards to the mounds which portrayed them as a consistent cultural identity that persisted for 1300 years.

The Process of Creating a Model

Discontented with the explanation of the mounds, Mallam began to work on the Iowa effigy as an individual study, rather than as an extension of Wisconsin. Firmly believing that the reason so little was known about the mounds was because people had been asking the wrong questions, he sought to move away from the study oriented in the artifacts associated with the mounds by gathering a more complete, accurate body of data and ultimately creating an interpretive model of the phenomenon.

By working with previous research notes such as the surveys by Lewis and Orr, Mallam began his work to study and preserve the Iowa effigy mounds. In 1971, he pioneered an innovative method of recording and surveying mound formations. He and a student crew began outlining the effigy mounds in lime and taking aerial photographs with the hopes of being able see patterns within and between mound groups. Major aerial photography began in 1974, and by the end of the Luther College Archaeological Research Center survey, there was a complete compilation of 53 Iowa effigy mound complexes which were all located within the Driftless Area. Given this observation along with his own ideology, Mallam staunchly argued for the interrelatedness between environmental and cultural variables as one of the primary contexts for interpreting the mounds.

In order to arrive at an interpretive model, Mallam first had to gather more quantifiable data. In order to obtain data points to be able to categorize individual mound forms, he used a polar grid system. This meant that the categories were contingent on the accuracy of data represented rather than an “individual determination” of a form’s resemblance to an animal. Factor analysis was then used to simplify the variance expressed in the data along with various histograms. This information along with topographic features was used in determining mound complex patterns which, in almost all cases, assumed linear arrangement. These analyses showed that variation of mound forms within an individual site was determinately less than the variation between sites.

The Effigy Mound Manifestation

In his 1976 thesis, The Iowa Effigy Mound Manifestation: An Interpretive Model, Mallam published his research. He interpreted the mound complexes as integrative mechanisms, or “large public work efforts,” the cultural means through which political, economic, social, and religious activities were seasonally organized in response to predictable annual occurrences of natural resources along the Mississippi Trench. He concluded that 83 percent of the mounds surveyed were located along or within two miles of this trench, a location which coincides with an environmental zone that possesses a high density and variety of natural resources. Politically, he asserted that the mounds may have functioned as territorial demarcations.

For Mallam, the mounds primarily represented symbolic behaviors; they were places to which people annually returned for social reinforcement and renewal. He hypothesized that groups would scatter and move along the valley to survive, then return to the river where mound building became an integration exercise to reinforce what they commonly believed. According to Harvey Klevar, Mallam saw the mounds as “places thankful to mother earth.”

Mallam’s Hypotheses

Hypothesis I: Each of the Iowa Effigy Mound complexes was constructed by a separate social group. Therefore, similar mound forms from different complexes will be more likely to be heterogeneous in form than similar mound forms within the same complex.

Hypothesis II: The function of the Iowa Effigy Mound complexes is a consequence of the relationships occurring between the distribution of natural resources in northeastern Iowa and the political, economic, and religious needs of hunters and gatherers exploiting these resources.

Hypothesis III: The subsistence-settlement pattern of Iowa Effigy Mound sociocultural groups was characterized by Primary Forest Efficiency, Intensive Harvest Collecting, and annual social coalescence and dispersal.

Current Research and the Effigy Mounds National Monument

Today the Effigy Mounds National Monument also label the 200 plus mounds preserved in the park as “sacred space” and is affiliated with 18 American Indian tribes. They affirm that clues as to what the mounds represent can be found in legends and mythology, which describe the effigy mounds as ceremonial and sacred sites. To a lesser extent, they acknowledge that scientific research can also provide insight and that some archaeologists believe the mounds were territorial demarcations, but much of the data is still inconclusive.

LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging)

This remote sensing technology has the ability of mapping features hidden beneath vegetation with the use of lasers, and can give an overview of broad continuous features that might be indistinguishable from the ground. In the years 2007-2010, the University of Northern Iowa conducted the Iowa LIDAR Mapping Project as part of a U.S. geological survey, thereby creating a database of LIDAR images for the entire state. LIDAR is especially gaining popularity within the archaeological community as it is non-destructive and can provide the ability to create high-resolution digital elevation models of archaeological sites that can reveal micro-topography which would otherwise be hidden.

This portion of the exhibit was completed by Lisa Stippich (’14).

The Mystery of the Serpent Intaglio

In 1982, R. Clark Mallam went to Lyons, Kansas for his year long sabbatical to do research on the serpent-like structure in the prairie near the town. Clark believed that the structure was an intaglio built by the prehistoric peoples who lived in the area.

Evidence to Support His Hypotheses

While excavating a section of the Serpent, Clark found two chert flakes (a flake is the debris from making or sharpening a stone tool) which suggests that prehistoric peoples did construct this feature.

Art Bettis, a soil expert who helped on the project, found that the layers of different soil colors show systematic changes across the feature which is supportive evidence for the human modification of the area. However, Bettis did note that the differences were quite subtle and that more research would need to be done on the feature.

Clark also noted that the bluff ridge on which the serpent is located is large enough to accommodate its form in any direction. The prehistoric peoples chose to position it 20 degrees west of north. The serpent’s orientation connects to the nearby village sites, known as the Council Circles.

The Serpent and the Council Circles

Clark discovered that the “jaws” of the serpent included the three Council Circles in the outward extension of its alignment. On June 21st, the longest day of the year, the sun sits in the open mouth of the Serpent. The sun is a representation of life for the prehistoric Great Bend culture and thus the serpent holds life in its jaws. Clark believed that this intaglio served as a metaphor for life.

This portion of the exhibit was completed by Cassie Kubicek (’13).

The New Galena Enclosure

The New Galena Enclosure is one of the last remaining archaeological features of its kind in northeast Iowa. It was originally discovered by Theodore H. Lewis and documented by Ellison Orr as part of his early 20th century survey work. Luther College’s Dr. R. Clark Mallam relocated the site in 1985 using Orr’s information and found it to still be in good condition.

To the Cage and Back

In the fall of 2014, our student workers put together a series of exhibits of their favorite objects from our collections, most of which are stored in what we affectionately term “The Cage.” Our exhibit “To The Cage and Back” was designed to highlight some of the objects that have not been shared with the Luther community for some time and that were of particular interest to our student workers for a variety of reasons. Though only fifteen objects were chosen, they come from across the world and span thousands of years. From a Cameroon bow to a pair of Inuit baby moccasins to French bank note, come explore some of what the anthropology collection at Luther College has to offer.

Numismatics

Numismatics, or the study and collection of coins, currency, and medals, make up one part of our collections here at the Luther College Anthropology Lab. One of our student workers is conducting a full inventory of the collection and picked a couple of her favorites, while another chose an ancient Greek coin recently transferred from the anthropology collections to the Classics department.

1896 Presidential Campaign Token (N433), “Sound Money”

Metal

United States, 1896

Numismatic Collection, N433

Donor: Unknown, donated ca. 1900s

This token was designed for the 1896 presidential election between William McKinley and William Jennings Bryan. Produced by the McKinley campaign, it focuses on the biggest policy issue of the day: whether or not cheaper silver should be implemented to back U.S. currency rather than the gold standard. Bryan, a “Silverite,” endorsed the idea of silver coinage, but McKinley argued that the resulting inflation would further harm the economy of the country already in a severe depression. McKinley won the presidential election of 1896, in part due to his effective campaign to defeat the free silver proposal.

This token portrays the iconic American eagle in two positions, the first posing proudly accompanied with the statement “I’m all right” to show that America would be prosperous and economically stable by maintaining the gold standard for currency. The token’s reverse in this position declares: “Sound Money: Means A Dollar Worth 100 Cents”

When the token’s icon is rotated, the eagle bends its head, its body is distorted, and the slogan changes to say, “Where am I at?” to convey the risk that Americans would be taking if the free silver plans were implemented. The reverse in this position declares: “Free Silver: Means A Dollar Worth 50 Cents”

Why I Chose It

My project for the Anthropology Lab is to complete a full inventory of the Numismatic Collection. Part of this collection includes campaign tokens and most are rather simple with some “vote for me” logo. This particular piece in the group of U.S. medals and campaign tokens caught my eye first because it is a brilliant gold color, and second because it features a movable part.

– Kelsey Williams ‘15

Pegasus Coin (HV 51), ca. 4th century BC

Metal

Ancient Greece, ca. 4th Century BC

Ancient Coin Collection, Classics, HV 51

Donor: Mr. Hatthvedt

The invention of coinage allowed for easier trade by fixing values through weight, and was later marked by different stamped images like turtles, lions, and bulls. Ancient Greece’s coins were issued by the separate city-states and can be identified by the different images depicted on them. These images would relate to the city’s history, mythology, and characteristic products.

Corinth depicted Pegasus on many of its coins due to the myth of its ancient king Bellerophon taming Pegasus with the help of a golden bridle given to him by Athena. This coin is recognizable as Corinthian by the letter Koppa beneath the front legs of Pegasus. The Koppa is a symbol for Corinth which had the spelling Ϙόρινθος.

Why I Chose It

My interest in Luther’s ancient coin collection began while working on my senior project which focuses on the iconography of doves in Roman coins; it has however spread to a wider range of cultures and time periods.

– Regina Preston ‘14

French Bank Note: Territorial Mandate

Paper and Ink

France, ca. 1796

Numismatic Collection, N419

Donor: Unknown, donated ca. 1900s

This object is a bank note from France in the late 1700s called a Territorial Mandate. The creation of this note was meant to stimulate the troubled French economy and was designed to be a challenge to counterfeit. However, the bill did not last a full year before it was removed from circulation. The bill proved very easy to forge and very few people wanted to use it while the old bills were still in circulation. In the course of a week this bill was worth 1/10th of its original value, causing it to become widely unpopular and removed from circulation rapidly.

Why I Chose It

I chose this bill because of the fascinating story surrounding it. It absolutely blew my mind that this bill could lose value so quickly while other forms of currency continued to do well in the country. I also was intrigued by the fact that a bill worthless in the past could be priceless now because of its failure.

– Kelsey Williams ‘15

The Americas

Birch, Spruce, Cedar, Pitch

International Falls, Minnesota, United States

Ethnographic Collection, E525

Donor: Rev. R.O. Evans, donated 1924

By 1922, Luther College owned a museum curated by Dr. Knut Gjerset, who added to the collections by requesting artifacts from Luther alumni living around the world. In early 1924, Reverend R.O. Evans exchanged letters with Gjerset about getting objects for the museum’s Indian Collection since Evans had frequent contact with a respected trapper fluent in the language of Ojibwa, the local tribe. On the trapper’s recommendation that an Ojibwa canoe would be “the very finest specimen” for the collection, Evans commissioned a birch-bark canoe for $25.

Ojibwa canoe-builders took a period of four months to build one canoe, using materials found in their Great Lakes environment. Birch trees provided large swaths of water-repellant bark, spruce tree roots provided flexible and strong stitching material, and cedar lumber provided the strong skeleton of the canoe. After harvesting the wood materials, the builder soaked strips of cedar, curved them, and dried them into the proper curves, a process that took about three months.

The actual building process took the last month and started with the following steps: creating the gunwales and thwarts from cedar, pounding a series of wooden stakes into the ground in the shape of the gunwales, and lacing together bark pieces inside the stakes. Next, the builder filled out the hull by inserting flat cedar strips lengthwise and the curved cedar ribs crosswise inside the bark. He then secured the canoe’s shape by lashing the gunwales and thwarts to the canoe’s hull. The last step was applying pitch, made from spruce gum, to waterproof the sewn seams.

On July 4th, 1924, two Ojibwa women paddled Luther’s new canoe thirty miles north. After hiring a truck to haul the canoe to International Falls, Minnesota, Evans then had a freight box built for the canoe and shipped it via train to Luther College. The cost of the canoe plus shipping was $35. The canoe arrived in Decorah in late July 1924.

Why I Chose It

In February 2011, I took my first tour of the space in the library basement used by the Luther College Anthropology Laboratory to store its collections. Among other interesting artifacts, I saw the two-person, birch-bark canoe owned by Luther College. Afterwards, I had forgotten all about it until I spent the next summer guiding back-country canoe trips in northern Wisconsin and Minnesota.

After one summer working there, I’ve continued working each summer as a guide, learning about the cultural interactions between French-Canadian Voyageurs and the local Ojibwa tribe. I guided with a reconstructed canoe known as a “Montréal” canoe. Voyageurs used Montéal canoes, which are more than twice as long as a typical two-person canoe, to travel the Great Lakes and larger rivers. They created these canoes by adjusting the template of an Ojibwa long-nose canoe. After guiding trips with a canoe reconstructed from French-Canadian Voyageur history, I returned wanting to learn more about Luther’s canoe.

— Jess Landgraf ’14

Pueblo Tourist Bowl, E428

Clay

Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico, United States

Ethnographic Collection, E428

Donor: M. Kathleen Daly, donated 1971

This earthenware bowl is colored with commercial poster paint made by the Tesuque Pueblo. Traditional Puebloan pottery was used locally and techniques included the painting of design before firing. Although this bowl shows some traits of traditional Puebloan pottery, this one was made for tourists. The colors are brighter and were added after firing.

In the late 1800s, the Pueblo people were having a hard time meeting their needs, so they started to sell their pottery and handicrafts. These sold well, so they began to make their pottery exclusively for the tourist market. At the time many museums and government institutions went to the Pueblo people to collect cultural objects. By that time, many traditional crafts were no longer available, so tourist objects like this are among museum collections.

Why I Chose It

I chose this object for display because after a semester of looking at rock and pottery for my senior paper, I wanted to see some color. This bowl is very bright and colorful compared to other bowls from my study. In addition, the Puebloan culture has an interesting history that I would like to know more about. As a child my grandpa would watch westerns all the time, thus I was drawn into the culture of the Native Americans.

– Kathryn Morehead ‘14

Tewa, Black Carved Pottery, Avanyu Design, E1021

Clay

Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico, United States, ca. 1930s-1983

Ethnographic Collection, E1021

Donor: Unknown

This ceramic bowl lacks an artist signature, but is typical of the ‘cameo style’ of carved black pottery made by the potters of Santa Clara Pueblo. This style was established in the 1930s by potters such as Rosalie Aguilar and Rose Gonzales. This pot was purchased at Sewell’s Indian Arts store in Scottsdale, Arizona some time before 1984, likely in the 1970s or 1980s according to the current owner.

The carved design depicts Avanyu, a Tewa deity and guardian of water. The Avanyu live in the waters of the Rio Grande River in New Mexico. This serpent has associations with lightning, as depicted with the zig-zag motifs in the iconography. Avanyu imagery also appears across the American Southwest as rock art, carved on canyon walls and in caves above the river indicating the important associations with waterways in the arid desert of New Mexico.

Why I Chose It

This stunning bowl reminds me of my fifteen years of living in the Southwest prior to my arrival in Iowa. My first southwestern archaeological project was near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico as a graduate student at Arizona State University in the 1990s. My current research in Mexico incorporates iconographic interpretations of pottery designs, including the mythical Quetzalcoatl, or “feathered serpent” which may be a distant relation to the deity depicted here.

– Dr. Crider, Collections Manager

“Alzate” Ceramic Effigy, E580

Manufactured Ceramics

Medellin, Colombia, South America, ca. early 1900s

Ethnographic Collection, E573-E578, E580-E581

Donor: Unknown

This collection of eight terracotta black ware effigies is aquatic animal-themed, displaying similar bulbous shapes, each with unusual yellow-orange soil deposits on the surface. These vessels have been in our collections for over forty years and their identity is lost… until now. Over several months early in 2014, we extensively researched the origin of these unusual pots. We suspected that the pieces were Central or South American and possibly Pre-Columbian antiquities. Thanks to the Curator of Collections at the Logan Museum of Anthropology in Beloit, Wisconsin, we learned that they were from Colombia and were part of a famous collection of forgeries now called “Alzates,” named after the family who manufactured them.

“Alzate” Ceramic Effigy, E576

During the late 19th century, anthropology was emerging as an academic discipline, and the collection of artifacts from lost or ancient cultures was popularized by wealthy collectors. Don Julian Alzate, a taxidermist and known tomb raider from Medellin, Colombia, began making these ceramics along with his two sons. Quickly their “Alzates” were distributed as genuine pre-Columbian artifacts due to the support of the well-known collector Don Leocadio, a family friend. Don Leocadio bought thousands of them to fill his own museum, believing them to be authentic antiquities. The Alzate family went to great lengths to provide evidence of their antiquity, taking collectors on digs to “discover” the ceramics in grave sites. The Alzate family successfully deceived the academic world until 1914, when Eduard Seler decried the Alzates as frauds at the First International Ethnographic Congress. It was not until 1920 that these objects were publicly denounced as forgeries in a Colombian newspaper.

“Alzate” Ceramic Effigy, E574

Why I Chose It

I chose this collection of artifacts because they were very mysterious and appeared to be really old. I was hoping to prove that they were in some way historically significant to make up for their unpleasant appearance. As it turns out, these objects have an interesting historical relevance and now they can be used for examples of antiquities forgeries and also as folk art in their own right.

– Katie Gove ‘14

Alaska

The majority of our collections from Alaska are ethnographic in nature and part of the T.L. Brevig Collection. Brevig, a Luther graduate of 1876, was a missionary and teacher in Teller, Alaska who worked with the Inupiaq or Inuit people and a group of Norwegian Laplanders, the Sami.

Snow Goggles, E207

Wood

Brevig Mission, Alaska, United States

Ethnographic Collection, E207

Donor: Rev. T.L. Brevig, donated ca. 1894-1916

The first use of snow goggles in North America is attributed to the ancestors of the modern Inuit, the Thule people (AD 1000-1600). Eskimo groups such as the Inupiaq used snow goggles to help reduce snow/ice glare and exposure to the harsh Arctic sun, which can cause snow blindness, a condition that causes temporary blindness and may result in permanent eye damage. The goggles are crafted from a single piece of wood, bone, or leather. Oftentimes, the inside of goggles will be burned or painted black to further reduce the glare. The narrow slits limit the wearer’s field of vision, reducing the amount of extra light entering the eyes and improving visibility in a snow-covered environment, which especially helped hunters find their prey. This was especially important during the spring when the Arctic sun is at its peak, sometimes reaching 24-hour periods of sunlight.

Why I Chose It

On one of my ventures into The Cage, I came across a box with a bunch of really cool Inupiaq artifacts, including seal calls and intricately carved ivory pieces. I saw this tiny little thing tucked away, snug in its own little compartment. Given its small size, it took me a minute to realize that it was a set of snow goggles. As a skier, it’s pretty cool to see the drastic change in design from modern snow goggles and learn that the original models were highly effective.

– Emily England ‘15

Needle Case, E661

Ivory and Wood

Brevig Mission, Alaska, United States

Ethnographic Collection, E661

Donor: Rev. T.L. Brevig, donated ca. 1894-1916

The needle case is primarily made of ivory but has a wood stopper at one end. Needle cases were often designed and carved by men to be given to their wives and portray images of Inuit life. The cases were a source of pride and sentimental value for each woman. Inuit women would have used needles for the never-ending sewing and repair work on clothes, blankets, and all kinds of other materials. Each Inuit tribe would carve in different styles and patterns. The needle itself would have been attached to a leather strip that would be able to be pulled in and out of the case for easy use.

Why I Chose It

I chose this artifact because I was very interested in the intricate designs and pictures on the very small object. When I first found the needle case, I had absolutely no clue what it was or what it could have been used for, but I was drawn to the carvings. I wanted to understand why someone would spend so much time and effort carving a tiny piece of bone. In the end I found it to be very sweet and almost romantic that the men would carve these small needle cases for their wives. The Inuit people turned a functional item into a beautiful piece of artwork that could be shown off to others in their community. The idea that they took the time to make these intricate carvings is remarkable to me.

– Ally Lothary ‘16

Inuit Baby Moccasins, E2006.26

Leather, Fur, and Beads

Juneau, Alaska, United States

Ethnographic Collection, E2006.26

Donor: Jane Kemp, donated 2006

Moccasins vary in size, but are recognizable as clothing items for Native Americans across the country. Though made of similar materials, soft leather stitched together by sinew, the different patterns, cuts, and decorative beadwork, quillwork, fringes, or painted designs actually served as a way to differentiate between tribes. Moccasins were used as everyday footwear, made to be durable and comfortable and designed to protect the wearer’s feet from the harsh outdoor conditions and be stealthy during hunting. The Inuit were known for their invention of the heavier-duty boots called mukluks, which were made of sealskin, fur, and reindeer hide and frequently lined with rabbit fur for added warmth.

Why I Chose It

Having been new to the anthropology lab, I decided that the best way to become more familiar with the collections was to spend some time wandering through the storage facility, or “The Cage” as it is affectionately called. While going through the ethnographic objects, I found so many really interesting items from all over the world in our collections, but for some reason I kept coming back to the same box with these tiny baby moccasins. I would repeatedly open the box to just stare at them, or show whoever happened to be in The Cage with me. Not only did they prompt an “Awww!” from everyone due to their sheer adorableness, but they also showed such great craftsmanship in the intricate beading and small nature of the object. Although I’m sure stealth while hunting was not the intent for this pair of moccasins, they definitely would have kept little toes warm.

– Callie Sonnek ‘15

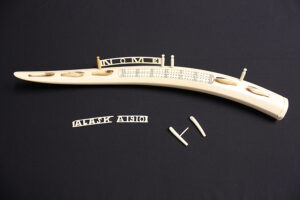

Cribbage Board, E262

Ivory

Nome, Alaska, United States

Ethnographic Collection, E262

Donor: Unknown, donated 1910

Most of the Inuit today live near the coast of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Siberia. They depend on the sea for food, and family is the most important aspect of Inuit society. Before the 19th century, when the Inuit fashioned tools, weapons, and religious or ceremonial items, they used the limited number of materials available to them—walrus ivory, bone, driftwood, stones, and skin. Today, these artifacts are considered “art” because of their beauty and intricate designs. This high quality of design came from a need to please the unseen spirits at the time they were made. The Inuit began to make more objects specifically to sell to European whalers in the 19th century. This included highly decorative pipes and walrus tusk cribbage boards, like this one. Still considered some of the finest examples of Inuit work, this tradition of excellence in craft continues among modern-day Inuit.

Detail of bottom of cribbage board, E262

Why I Chose It

The first time I was exposed to cribbage was a fifth grade tournament. I was not very good at the game, but it was good for working on my arithmetic. Ever since then I have been fascinated with the game and its history. The game of cribbage is believed to be invented by British soldier and poet Sir John Suckling in the 17th century. It was very popular among English settlers in the American colonies and eventually became a staple among sailors and submariners for hundreds of years, especially in the Navy during World War II. Although the game has declined in popularity over the last 50 years, many people I know still have an old cribbage board in their basement or on the back of a shelf. When I saw this Alaskan cribbage board, I was transported back to fifth grade and I wanted to play again! The coolest part of this board is the storage for the pegs, which is a little drawer underneath the right end of the board.

– Rachel Wiebke ‘16

Wood, Seal Claws, and Leather/Sinew

Alaska, United States

Ethnographic Collection, E186 and E194

Donor: Unknown

Seals are comforted by the sound of other seals on nearby ice. These ice scratchers allow hunters to mimic the sound of seals on ice by making a series of fast short scratches on the ice. The pattern and sound lulls alerted seals into a sense of security which allows the hunter to approach. The scratching sound may also attract seals from farther way. Given the effectiveness of the technique, it is still used today, though hunters use different and less specialized tools.

Seals are an important resource for coastland cultures in the far north. Nearly every part of the seal was used by the Inuit: the seal meat provided a valuable food source, the seal skins were used to make clothing, blankets, tents, and boats, seal blubber was a fuel, sinew made cords and ropes, and the bones and various internal organs were used for making hunting equipment and other tools.

Why I Chose It

I chose the ice scratchers because they were some of the most intriguing things in the box of Alaska artifacts in the collection. I didn’t know their function, but research revealed both their function and the many different styles of ice scratchers that exist. Some are all carved wood and others have many seal claws. It was interesting to learn about the importance of the seal to the Inuit and how increasing environmental regulations with seal hunting has affected the Inuit and their relationships with international governments. The seal is so important that the Inuit are exempt from several modern governmental protections for seal hunting as a reflection of its importance to their cultural heritage.

– Emily England ‘15

Asia, Africa, and the Middle East

Fez, E866

Felt Cloth, String

Turkey, Middle East

Ethnographic Collection, E866

Donor: W. Magelsen, donated 1901

The fez takes its name from the Moroccan city of Fes, which served as its primary place of manufacture. This site is the origin of the berries used to create the crimson color that decorated this headwear which became fashionable across the Ottoman Empire in the 17th century. Sultan Mahmud II adopted it as part of the military uniform in an effort to modernize, banning the turban which had been the popular fashion of the time. Wearing the fez spread in popularity, becoming a symbol of the region. At the turn of the 20th century, its influence spread and it became a fashionable accessory in the luxury smoking outfit in the United States and Britain because of its “exotic” cultural associations. In 1925, in an attempt to modernize the image of the country, the Turkish president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, passed legislation to imprison men for wearing the fez.

Why I Chose It

“It’s a fez, I wear a fez now. Fezzes are cool.” –The Doctor

My love of the long-running British television show Doctor Who is what brought me to this object initially. The Eleventh Doctor, played by Matt Smith, is full of random obsessions, one of which is this particular style of hat. I found this object endearing due to my J-Term study abroad experience in Turkey. I became increasingly fascinated by Turkish culture and enjoyed the chance to immerse myself in this historically rich nation. Although the men of Turkey no longer wear the fez as part of their everyday dress, it still brings me back to the many great memories I have of traveling in this exciting country.

– Callie Sonnek ‘15

Geisha Neck Pillow, E732

Cloth, Dried Leaves, Wood

Japan, Asia

Ethnographic Collection, E732

Donor: Unknown

Geishas were traditional female entertainers skilled in music, dance, and the art of dialogue. Geishas-in-training were called maiko, and marked their identity as distinct from fully-trained geisha through excessive hairdressing and face paint. A maiko headdress weighed roughly 6 pounds, took hours to make, and was generally only unraveled once a month and hair washed thoroughly. Special pillows like this one, called takamakura, were needed to keep their elaborate hairstyles intact while sleeping. For the sake of the art and effort taken into forging the difficult hairstyles, the maiko had to sleep completely still on these pillows.

Based on the materials and its condition, this pillow is likely from the early 20th century, before Japan’s loss in World War II brought an end to such traditional arts of the geisha. It was a profession held in high esteem, especially during the Tokugawa Shogunate (or Edo Period, A.D. 1603-1867) until western influence brought new arts to the country.

Why I Chose It

This object is of interest to me due to my love for Japanese culture, both traditional and modern. I studied abroad in Japan during the 2012-2013 academic year, during which my fascination with Japan grew. The transformation of their culture from the old to the new after WWII and the quick advancement to becoming one of the most technologically advanced nations in the world while still maintaining old components of expression has always been a source of amazement for me. This geisha pillow represents a small part of an old world so very different from the Japan we see today.

– Emily Griffin ‘14

Steel, Ivory, Wood

Japan, Asia

Ethnographic Collection, E728

Donor: O.B. Stephens, donated 1931

The tantō is a traditional Japanese short sword that was invented during the Heian period (A.D. 794 – 1185) as a practical weapon. Traditionally, a tantō would be no more than one shaku (30cm) in length and forged in a hira-zukuri style, meaning that the blade is essentially flat without a ridgeline. As tantōs became more prevalent during the Kamakura period (A.D. 1185 – 1333), increasingly intricate designs developed on the sheath and handle.

During this time the tantō served as an auxiliary weapon, the shorter of the two swords worn by the samurai. Later, during the Edo period (A.D. 1603 – 1867), the tantō became the focus of one of the central martial arts practiced at the time called tantojutsu.

This tantō in our collection is one of the more embellished examples of this weapon, likely dating from the Edo period.

Why I Chose It

I chose this particular object from the ethnographic collection as I have a deep, long-standing interest in Japanese language, culture and history, especially with regards to the shogunate.

– Lisa Stippich ‘14

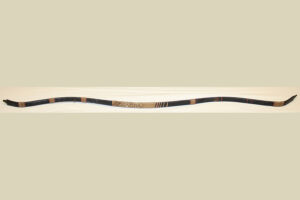

Cameroon Bow, E310

Wood and Cord

Cameroon, Africa

Ethnographic Collection, E310

Donor: A.E. Gunderson

This item was donated by Adolphus Eugene Gunderson, a graduate of Luther Seminary. He started work as a missionary in Africa in 1912 in Nigeria, though his dream was to work in Sudan. After returning from his first African mission in 1916 he started campaigning to begin work in Sudan. However, WWI made this impossible. Instead, he went to Cameroon to establish a new mission. This became known as the Sudan mission because of a possible Sudanese dialect spoken by the local people. These people are known as the Gbaya, who live in central Cameroon. Unfortunately there is very little information on the Gbaya. During his time in Cameroon he collected a number of items from the local people; one of these was this bow. The bow would have been used for hunting and/or warfare.

Why I Chose It

I found this object fascinating because I have an interest in warfare archaeology. Weapons technology, while being only a small part of warfare, is still extremely interesting to me. After selecting this object it only became more intriguing because it is something of a mystery as I could not find any information on the culture the item came from.

– Phil Cleven ‘14

All the Small Things

In the earliest times of the Inuit people, around 2200-2000 B.C, a tradition which is now known as the Arctic Small Tool tradition (ASTt) began to develop. This tradition is generally considered the cultural basis for the later Inuit of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. The Luther Anthropology Ethnographic collection houses objects from Alaska, most collected during the latter part of the Inuit Historic Period ranging from 1770s – 1940s. At this time the Inuit peoples were making their first contact with Europeans and they began crafting items specifically for trade. The items became larger, more delicate and the decoration of the items were intentionally artistic, portraying traditional life and themes. However, their personal objects were often small enough to be carried on their person, while the larger items were necessary to hunt or build shelters. It is in these small items that we see the Inuit material culture as an expression of their long survival of the harsh Arctic landscape and nomadic lifestyle.

Personal Items

Earrings (Alaska, E683) and comb (Alaska, E177)

Personal items were not common among the Inuit people. As a nomadic people they carried with them what they could, so personal items often showed wealth and status. Some jewelry would be used specifically for rituals. Some of these personal jewelry items such as earrings and necklaces were often made from ivory or antler. Earrings and necklaces would also utilize other stones such as amber or turquoise, shells, beads and metals such as copper or silver. Combs typically made from ivory or antler may have served two purposes, to comb through hair but also to prepare skins.

It was the role of the women to care for children, prepare food, and sew clothing. The Inuit were constantly moving, working, and hunting, activities which made their clothing susceptible to tears and holes. Inuit women were regularly sewing and repairing clothing and blankets as these items were much needed for warmth. Sewing kits were invaluable for keeping tools together and would contain many objects including: a thimble, needles, an awl, spools of thread, and a moccasin creaser. These items would be tied together via caribou sinew thread and then tied to a belt, attached to the drawstrings of her coat, or hung around her neck. Needle cases were carved by their husbands and decorated with images ranging from geometric shapes to depictions of day-to-day life.

From left to right: Small seal bead (Alaska, E689), seal head bead (Alaska, E679), trio of beads (Alaska, E690), and large seal bead (Alaska, E668)

Beads were often made from ivory, bone, or shells. They were commonly found on clothing, often decorating the shoulders and front flaps of jackets, as well as on shoes and mittens. The design of the beads ranged from small, nondescript squares to animal shapes. Occasionally, strings of beads were used to attach objects such as pipes or tobacco pouches to belts.

Clockwise, from top left: Small seal figurine (Alaska, E687), large seal figurine (Alaska, E670), polar bear figurine (Alaska, E669), and whale figurine (Alaska, E671)

The Inuit carried with them small charms or fetishes. Their exact purpose is still unknown to some degree. Many of the Inuit informants hold that they were used as good luck charms for hunting and protection against illness and injury. Others say they may also have been used as game pieces, objects used to illustrate legends, history, religious beliefs, or used in shamanic rituals. Here we see a variety of marine animals carved from ivory that functioned in this manner, as charms or fetishes.

Survival

Living in the Arctic, where temperatures can drop as low as -58 °F during winter months, items of warmth were essential. The Inuit developed a wardrobe to survive the low temperatures with caribou parkas and pants. Socks were often made from grass that served the dual purpose of providing warmth as well as drawing out moisture. Boots were made from a variety of materials such as seal skins; salmon skin was also used along with the furs from caribou. To be successful, they needed to be warm and waterproof. They often had hard, high-crimped soles. Shoe design varied from tribe to tribe and went as high as the knee or higher and then tied onto their jacket for support.

Subsistence

The Inuit’s staple food was seal, but they also hunted walruses and whales and fished for salmon. Fishing lines were made from plaited deer or caribou sinew. They used many styles of hooks and harpoon heads. Lures were carved from ivory or bone in the shape of fish. The harpoon was an invaluable weapon to hunt animals such as seals, as they were designed to pivot sideways upon entering the prey, holding onto an animal while it was pulled towards the hunter. The size of the harpoon head varied depending on what was being hunted. While hunting from a kayak, the harpoon head would often be larger than if they were hunting from the ice.

From left to right: Harpoon head (Alaska, E174), fishing hook (Alaska, E230), small harpoon head (Alaska, E175), fishing hook (E682), and harpoon head (Alaska, E229)

Other items used during hunting were plugs and qanging. Plugs were used to plug the wounds on a seal made from the harpoon. This would stop the bleeding but also help preserve the animal’s flesh from decay. It was pushed into the wound, under the skin. A qanging is a piece of ivory or bone that was carved into one of many different shapes—some resembled seals while others were ‘Y’ shaped. They were used to secure a thong that had been strung through a hole in the seal’s throat and mouth. This was then used to tie the seal to a buoy or kayak.

Inuit yo-yos. Juneau, Alaska. E1033, E1034, E1035, E1036

Hunting was an important skill for Inuit men, learned through a variety of games or toys played during childhood. The Eskimo or Alaska yo-yo is a toy that resembles a bolo, which is a weapon used to hunt birds. These toys helped boys to develop skills like dexterity, speed, aim, coordination, strength, and stamina. The object of this toy is to get the balls swinging in the opposite direction at the same time.

This interpretive display was created by Clara Miller (’15), exhibited on third floor Koren in 2015.

Native American Pipes

In many Native American religions, both past and present, the Sacred Pipe has special meaning and origins. Each part of the pipe has a special purpose and symbolic meaning. In some religious ceremonies, the purpose of the smoke is for an offering to the spirits, and inhaling the smoke allows for communication with the spirits. The stem of the pipe was pointed in the direction of the spirits and attracted them towards the ceremony.

The Sacred Pipe in the Lakota Creation Story

Pipes are often found in creation stories in native religions, such as the Lakota religion. In the Lakota creation story, a buffalo calf woman comes to Earth and gives the Sacred Pipe to the Lakota in order to assure health, welfare, and overall happiness of the people. After they received the pipe, the buffalo woman created the first ritual of the pipe, which was the Keeping of the Soul. This ritual was entrusted to one person, who was given the ceremonial duty of connecting with the Great Spirit through the smoke of the Sacred Pipe. It is a prominent position to be chosen as the Keeper of the Pipe, a right only given to select people in the tribe. The buffalo woman then disappeared into the sky, leaving behind a red pipe bowl in the shape of a buffalo as well as a stem made of wood adorned with twelve eagle feathers. This became the Sacred Pipe that is the central tool of the Lakota’s religious practices. Each religious ceremony in the Lakota religion begins with a Pipe ceremony.

One of the main symbols for Christianity is the cross, but for many Native Americans religions the symbol of their religion is the pipe. Even today, these religions, now practicing a hybrid of native religion and Christianity, use a pipe to symbolize their religion. The pipe symbolizes the transitional periods, such as the movement onto reservations, in the history of Native Americans. It also represents the preservation of their culture and religious traditions. The pipe was present and plays a large part in the creation of numerous native religions. Today, there is frequent use of both the cross and the pipe to embody the native religions and culture.

History of Native American Pipes

Pipes have been made and used for thousands of years. There have been many stone and ceramic pipes that have been found by archaeologists throughout North America dating back to 4000 and 3000 B.C.E. It is still contested among scholars when pipes started being used for ritualistic purposes rather than recreational, but the earliest known European illustration of a Sacred Pipe dates to 1591. This drawing was a depiction created by a Flemish artist named Theodore de Bry, after learning about a 1564 exploration of La Florida by French explorers René de Laudonnière and Jean Ribault. De Bry created engravings as well as this illustration based off French artist Jacques LaMoyne’s drawings of the exploration.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, pipes became a central tool for forming social and economic bonds with European settlers. They were used in trade as well as political and social negotiations. Europeans were captivated with tobacco and smoking. Native Americans and Europeans were able to use smoking as a shared recreational activity as well as a means for exchange. However, many problems came out of this trade system. Native Americans attempted to make social alliances through the shared interest of tobacco, but the European settlers were more interested in the economic benefits. The Europeans started to dominate the tobacco and pipe trading system. This was not the only way the Europeans monopolized the livelihoods of Native Americans. By the 1900s, most Native Americans had been forced onto reservations and the possibility of sustaining a trade relationship had ended.

In Southwestern Minnesota there is a red pipestone quarry that has been used by Native Americans for over 3,000 years. The red stone found in the quarries is fairly soft and perfect for pipe making, and has been used by various Native American groups since at least 1200 AD. In the 1700s, the prominent Native American group using the quarry was the Dakota Sioux. It was not until 1836, when George Catlinite “discovered” the quarry, that trade between Natives and European settlers started occurring. Native Americans and American settlers used the quarry together for a time, until European settlers took total control of the quarry during the mid to late 19th century.

In the 19th century, manufacturing and trade steadily increased at the quarry. In the 1860s, catlinite pipes were manufactured by American settlers in order to trade with Native Americans. Between 1864 and 1866, over 7,000 pipes were manufactured for trading purposes by the Northwest Fur Company as well as private investors. It was at this time that Native Americans started being forced onto reservations, and many of the Dakota Sioux were moved west onto reservations in the North and South Dakota areas. One subgroup of the Dakota tribe, called the Yanktons, were pushed to the edge of the pipestone quarry during the mid-19th century. The Yanktons were not allowed to access the quarry which greatly decreased their economic standing, but in 1928, they finally received monetary compensation for their loss from the United States government after a ruling by the Supreme Court. In 1937, the government gave permission for all Native Americans to return to the land and to quarry the pipestone. Today, people are not allowed to quarry the pipestone without a permit from the government. The quarry is currently a national monument and education center for students in the area.

The styles of pipes in North America remained rather constant from around 40th century B.C.E. until 10th Century B.C.E.; with tubular pipes being the most common. It was not until around 700 B.C.E. that a calumet style elbow pipe appeared. From that moment onward, pipes continued to change in style and shape, and eventually even purpose. For the Midwest, the most common material that the bowls of the pipes were made out of was catlinite. Some pipes from the Great Lakes area were inlaid with metal from mines. Black stone pipes were also common but were not collected as frequently due to their less vivid appearance. The stems were usually made of softer wood materials such as sumac or willow.

Individually, each piece of the pipe has its own importance and symbolism. When separated, the pipe bowl and pipe stem have different meanings and significance. When the pieces are put together they form the pipe which then takes on new meanings. The stem’s size and shape determines its purpose. Longer stems were used for group rituals and meetings, while smaller stems were used for leisurely activities. The stem is said to represent male energy as well as creative energy. Colors that are painted on the stems have many different meanings, too. When using the colors red, green, blue, and yellow, they typically depicted a certain direction (North, South, East, and West). Porcupine quills and hairs of various animals were typically woven around longer stems. Sometimes pendants or feathers were placed on the stem for ritual ceremonies. The pipe bowl on the other hand represents female energy. The red color, from materials such as catlinite, can represent blood or life. The shape of the bowl itself illustrates the female body as well as fertility and childbearing.

Pipes were styled differently depending upon their use as well as their intended owner. Women’s pipes were generally smaller, with short stems and few decorations. Men’s pipes, for ordinary occasions, were slightly larger and better made than women’s pipes, but were still quite small. Ceremonial pipes or pipes made for chiefs were larger with long stems. They were elaborately decorated, with feathers or other ornaments attached.

Calumet

One specific style of sacred pipe is the Calumet. It was generally made with red pipestone or limestone, with a larger and highly decorated stem. These pipes were considered very sacred and were not supposed to be put together unless by a religious leader in a specific ceremony. Each Calumet looks different, and can only be identified this way when used in a religious context. Other highly decorated pipes were mostly manufactured for tourists and were not considered sacred.

Bowl Styles

There are six specific styles of pipes that have been found in the United States. Our collection includes many of the different styles. The elbow style pipe is one of the most common, and is simply a pipe that is bent. One subset of the elbow pipe is the effigy style, with a bent shape of an animal or human (object E886). The t-shape bowl is self-explanatory, with a straight piece followed by an inverted t-shape at the bottom (object E492). Our collection does not include the disc, circular, or straight style. The Keel Style has a short round base and tapers at the top. One unique version of the keel is the tomahawk style, which features a tomahawk weapon head as a bowl (object E512). The tomahawk could be used to cut as well as smoke from, but generally was used for more symbolic purposes than practical.

Effigy Style

The effigy style pipe bowl is a long standing and highly religious style. The animal depicted by the pipe bowl generally has a symbolic connection to the tribe it was used by. However, during the 19th century many effigy style pipes were manufactured for tourists and do not have the same spiritual implications. Pipes made for tourists were made in one single piece (stem and bowl connected), in order to distinguish them from sacred pipes, which were created in separate pieces. Eventually other tourist pieces were made as separate pieces to more closely replicate the Native American pipe, much like the fish pipe in our collection.

Pipe Bag

Most sacred pipes were kept in separate pieces and in a pipe bag when they were not being used. It was very important that the pieces of a Sacred Pipe were not connected after a ritual ceremony. The pieces were stored safely in an ornately decorated pipe bag in order to protect them. In some groups it was also important that the pipe bag was kept inside and away from the elements, since it contained very sacred items.

Art Among the Hmong

The Hmong are an ethnic group originally from the mountainous regions of Southeast Asia. They have been relocated throughout their history, but have still maintained a strong sense of cultural identity and independence. Most of the Hmong living in the United States today came from Laos.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Central Intelligence Agency recruited thousands of Hmong men to fight against the encroaching communist regime as part of the “secret wars” of Laos. As the communist regime gained control of the country after the war, Hmong soldiers and their families were persecuted for their participation against the regime and thousands of people fled their homes and villages to refugee camps located in places like Thailand.

The United States, along with other Western countries, received many refugees from the wars in Southeast Asia, including Vietnamese, Cambodian, Thai Dam, and the Hmong peoples. American non-profits, churches (many Lutheran), volunteers, and refugee sponsors helped refugees make the transition to life in the U.S. Hmong families began arriving as early as 1975 and today there are over 200,000 Hmong in the United States, mostly in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and California.

Decorah and other rural towns in Iowa were among the first destinations for many Hmong families. The Southeast Asian Refugee Services (later the Northeast Iowa Refugee Coordination Services) program was established in 1979 to coordinate support programs to help smooth the transition to a new culture and language. There were education programs for tutoring in English as a second language, job placement projects, and volunteers to help the Hmong navigate their new lives in Decorah. One important way that the Hmong families earned some income was to sell their handmade crafts and textiles, such as story cloths.

Hmong textile design was traditionally used for clothing, and contained an array of intricate shapes and designs. Following the war, Hmong women applied their skills to new textile forms that were intended for western audiences in order to generate income to help provide livelihood for their families.

Story cloth folk art likely originated in the Thailand refugee camps, as the Hmong refugees were encouraged by missionaries and United Nations workers to tell their stories through embroidered narratives. Hmong artists were supplied the materials while in the camps and sent completed cloths to the United States and other western markets for sale. As Hmong artists resettled to places like Decorah, they continued to make story cloths in order to provide income for their families.

Story cloths are hand stitched and embroidered, depicting different daily life scenes, animals, festivals, and more. They are usually brightly colored, including intricate embroidery. Many represent stories that demonstrate the rich history and tradition of the Hmong. Most well-known story cloths include images of refugees fleeing from the conflict or portraying scenes during the war, as well as showing agricultural practices. This cloth displays a variety of animals native to eastern Asia. Animals are an important part of Hmong tradition, and are incorporated into countless stories and folktales. Tigers, for instance, are featured in many Hmong stories.

In the case of our animal story cloth, many of these artists were learning English through bilingual programs and practiced on the cloths by labeling items or describing scenes. You also may notice the one line of Hmong writing, which describes the rat eating corn.

An interpretative display created by Jessi Kauffman (’16) and Rachel Wiebke (’16), exhibited on first floor Koren 2015.

From Empire to Colony

Many European countries sent missionaries to follow in the wakes of famous 16th and 17th century explorers. Norway was the first such country to establish a permanent presence among the Zulu people of southern Africa in 1844. Previous attempts to establish mission stations in Zululand had failed, but the Norwegians found themselves welcome after healing the king’s rheumatism. Missionaries and other settlers created a secondary economy and subculture in southern Africa. The missionaries sought to eliminate obstacles to conversion, promoted European cultural values over Zulu, and facilitated the loss of Zulu political autonomy.

The Zulu people lived on the grasslands of southern Africa’s interior, maintaining a life centered on herding cattle. Zulu people lived with their extended families in semi-sedentary villages called kraals, which featured numerous huts organized around a central cattle pen. Before colonization, Zulu political organization featured several chiefs holding roughly equal authority. Families expressed allegiance to chiefs by moving their kraals near the chief they supported.

In the mid-1700s, European merchants introduced new forms of economic trade to African tribes. The struggle to control trade with the Europeans created tensions and led to many wars between tribes including the Zulu. By 1816, Shaka, a Zulu chief, had emerged as a regional power, coercing other chiefs to submit to him. The Zulu Empire continued to be a regional power until the British annexed Zululand in 1884.

Norwegian missionaries in Zululand established mission stations, permanent compounds including churches, schools, and housing for the missionaries and Zulu employees. The first Norwegian missionary, Hans Schreuder, was alone; other pastors and their families joined him over the years. His successor in 1883 was Nils Astrup, joined by his brother Hans in 1884.

Hans and Nils Astrup had a unique relationship with Luther College; their brother-in-law, Laur Larsen, was the college’s first president. Nils hosted two of President Larsen’s daughters, Marie and Hanna, while they served as schoolteachers at the Schreuder Mission. After Marie’s death in 1897, Hanna returned to Decorah. She later published a book and donated her collection of Zulu objects to the college.

Prior to and during initial contact with Europeans, Zulu life was centered on cattle. Cattle were not only a source of food and clothing but also a measure of wealth and status within Zulu society. Cattle, by exchanges such as lobola and sisa, tied people together. Lobola, or bride price, was the number of cattle given to a woman’s father by her fiancé. Sisa was a loan of cattle to a poor family in exchange for their allegiance. A man’s herd size, wives, and sisa loans determined his wealth and status.

Zulu clothes were different than European clothes. Children regularly wore nothing, and women wore only a black leather skirt. Men wore a belt from which hung a snuff bag and had aprons in front and rear. While in the military, men wore large collars of cattle tails, with two more tails tied at their knees as shin guards, loincloths, and headdresses of ostrich feathers. Zulu clothing or lack thereof shocked most European newcomers to Zululand.

Mission stations required Zulus to wear the approved European-style clothing. By 1897, many women bought cotton for clothing, marking a success for the missionaries. In addition, colonial employers hired Africans only if they wore Western clothing, thus signaling their missionary education. However, Zulus masquerading as mission-educated took advantage of their employers. These men would find salaried work and work that job for some time, only to quit and return to Zululand. After their return, they would use the money they had earned to purchase cattle, entering the traditional cattle economy.

In 1873, the British colonial governor officially presided over the coronation of the new Zulu king, Cetshwayo, in exchange for his signature on a constitution calling for checks on his power. Cetshwayo ignored the constitution and violated his promises. After failed attempts at diplomacy, the British colonial army attacked, starting the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. In less than eight months, Great Britain defeated the Zulu and formally annexed Zululand as a colony in 1884.

Missionaries worked to make Christianity acceptable to Zulus, a process necessitating that obstacles to conversion be removed. After thirty years of little success, the missionaries began seeing the king’s authority as the last obstacle to mass conversion. The Norwegian Bishop of Missions mediated between the new Zulu king and the colonial government to arrange the former’s coronation. The coronation began a series of events that culminated in Zululand’s annexation by Great Britain. Ironically, these events had little effect on Zulu acceptance of Christianity; Zulus did not convert en masse as hoped.

This display was exhibited in Koren in 2012, converted for web exhibit 2013 by Jess Landgraf (’14).

Kamidana in Meiji Japan Households

The object titled as “Wooden Shrine” in the Luther College Anthropology Asian Collection most closely resembles a Japanese kamidana. Kamidana literally means “god-shelf” and serves as a place to worship the kami, often translated as “deity.” The small structure is also accompanied by a small figure that appears to go in the structure. This concept of worshiping kami and use of kamidana stem from the indigenous Japanese religion Shinto. Shinto experienced a strong revival by the Japanese government during the Meiji Era 1868-1912, when this piece was dated, as a part of Japanese Westernization and nationalism. Kamidana was an invention around the early Meiji or late Tokugawa Eras during the beginning of this rise of nationalism and State Shintoism. Because of the resemblance to a kamidana and because it was made during the Meiji Era, the object E388 was most likely built as a result of the Meiji Shinto Revivalism during the 20th century.

Though this particular kamidana is different, most kamidana are set up quite similarly to shrines and can be easily seen as a miniature shrine. Inside, both of these structures typically contain nothing except an altar with a mirror, but a shrine may contain certain regalia while a kamidana may have a charm. The same offerings can be made to both, which include rice cakes, vegetables, fruit, sake, and branches of the sakaki tree. Another of the similarities is the recommendation that before approaching and praying at the shrine and kamidana that one should cleanse himself to promote a feeling of purity.

The idea of kami is a concept of the Shinto religion, which is indigenous to Japan and is unique in that it is an exclusively Japanese religion. While kami is usually translated as “god” or “deity,” it actually has a broader meaning within Shinto. When one feels a sense of awe or exuberance when experiencing nature or almost anything such as literature or music, Shinto calls the power that comes from this feeling in people tama, mi, or mono. The presence itself is referred to as kami. Often natural places will have this powerful presence, in which case it is marked with a tori gate or a shrine.

The popular translation of kami most likely comes from its associations with a traditional practice that was more relevant to prehistoric Japan of appeasing the forces of nature. These forces of typhoons, earthquakes, and volcanoes are most certainly awe-inspiring and have enough power of their own to become personified. Similarly, other especially beautiful or awe-inspiring natural occurrences or locations inspire personification, which looks quite similar to the worship of a deity.

The worship of a deity and kami look similar in this context, but not quite so with a kamidana. There seems to be a lack of an awe-inspiring landscape in relation to the kamidana since it is placed in the home. However, if one remembers that kami sometimes refers to only the presence of that feeling of awe, the purpose of the kamidana makes more sense. The purpose of the kamidana is not always straightforward even to Japanese people themselves, but overall the purpose seems to be that they are inviting this presence of the kami into their home in hopes for good omens.

This particular kamidana however, is different from most kamidana. It is recognizable as a kamidana because of its miniature shrine appearance and because it is made of wood, but that is where the similarities end. Most kamidana, though intended as a small scale shrine, are larger than E388. Not only that, it is missing the common elements listed earlier of most kamidana, such as the mirror or the charm, and instead has a small deity-like figure which seems to go in the shrine, but is not a typical custom of Shinto.

Considering that kamidana are meant to be placed in the home, homeowners could have their own say in how they were arranged. They customized and arranged their kamidana for their personal worship. Ono, in her book Shinto the Kami Way, even explains that, “The size and quality will depend on the financial ability as well as on the faith of the head of the household.” Kamidana had the potential to become very personal forms of religious expression even though there is already an accepted general layout.

The inscription on the inside of E388 which differentiates it from most kamidana also clarifies this difference. There is more writing that is covered up, but the majority of it could be translated. It roughly translates as: “In my fifteenth year I offer [this kamidana], this land I live on, this figure [deity figure] I will keep safe, looking forward, I pray for good things, Hiroshi Yano, born in the seventh year and eighth month of the Meiji Period.”

This inscription reveals that this kamidana was given to this boy, Hiroshi Yano, in 1876 on his fifteenth birthday, most likely as part of the common celebration, the Coming of Age Ceremony.