Welcoming students, again and again, in new ways all the time

by Kate Frentzel

Efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 have radically reshaped how schools and classrooms operate, and this reshaping has hit teachers hard. Some have seen their workloads double as they prepare lessons for both in-person and remote learners. Others face obstacles in connecting with students under these new circumstances.

We checked in with several Luther grads working in education to see how things are going. Fellow teachers will recognize their struggles—and their dashes of hope—and non-teachers will find new empathy and respect for these intrepid, compassionate, adaptable shapers of young potential.

Kelli Gapinksi ’17

Special education teacher at Clear Lake (Iowa) Middle School

Kelli Gapinski ’17

What challenges have you faced during COVID?

In my classroom setting, masks have been challenging. So much of my students’ learning comes from seeing my facial expressions and my mouth as I form words and letter sounds. It’s also challenging when I speak, because the mask muffles the sound and some of my students already have difficulty hearing.

What has helped you navigate this time?

Being more gracious with myself. It can be frustrating when Zoom doesn’t work, or a well-thought-out lesson doesn’t go as planned. However, my mantra this year is focusing on what I can control. I can control how I show up for my kids. I can control the content I provide knowing that I am doing my best for each student on my roster.

Emily Anderson ’20

Language arts and literacy teacher at Central Middle School in White Bear Lake, Minn.

Emily Anderson ’20

How is your workload different from a typical year?

Implementing a hybrid model is no small undertaking. While teaching my in-person classes, I instruct a group of full-time distant learners simultaneously. It requires a large amount of time, energy, and digital competency to pull off. I work an average of two to three hours each night outside of the regular school day and anywhere from five to ten hours on the weekends.

What challenges have you faced during COVID?

Talk is an essential component of any language arts curriculum. It’s crucial that students have frequent opportunities to discuss with each other the books they’re reading and the stories they’re writing. Facilitating small-group conversation in a socially distant classroom where most students can’t move from their desks and the others are miles away via computer has been an obstacle. Using Google Meet and Google Documents to collaborate can be a solution, but the unreliability of technology often leaves at least a few students out, held up by a buffering screen (haunted by the classroom ghost, as we say!).

Do you think COVID will permantly affect how we teach and learn in the future?

I’m sure that our education system will change as a result of this year. Already, navigating so many different learning models has pushed teachers to revamp old lesson plans, be innovative, and embrace new ideas in ways they maybe didn’t before.

Luigi Enriquez ’17

Associate director of choirs at Iowa City (Iowa) West High School

Luigi Enriquez ’17

In a typical year, what do you love about teaching?

Certainly the atmosphere of the classroom—people chatting before class, using class as a time to be in company with people, making jokes and showing funny singing memes, hearing students come together in song. I also love having performances and sharing the work we do within the classroom to our wider community.

What challenges have you faced during COVID?

How do you teach singing through a pandemic? Ahhh! A lot of time has been spent on how we can safely sing in school, how we can still make this year exciting and a good experience for students, and also how we can make singing more accessible to our online friends. I’ve had to reconsider what is most important and valuable for students to know; I don’t want to overwhelm them with information, so I’ve chosen a few musical concepts to focus on each trimester. I’ve also had to cut down on how many songs we sing in a trimester, and have had to reconsider how we can still have a “concert” experience for our families and friends.

What has helped you navigate this time?

Human connection and social capital—this idea that we have each other’s back during the toughest challenges, that we can lean on each other when the going gets tough, that we can still be in community and learn and laugh with each other. Those have been the most valuable things for me.

Johanna Beaupre ’18

English language (EL), history, and English teacher at Osseo (Minn.) Senior High School

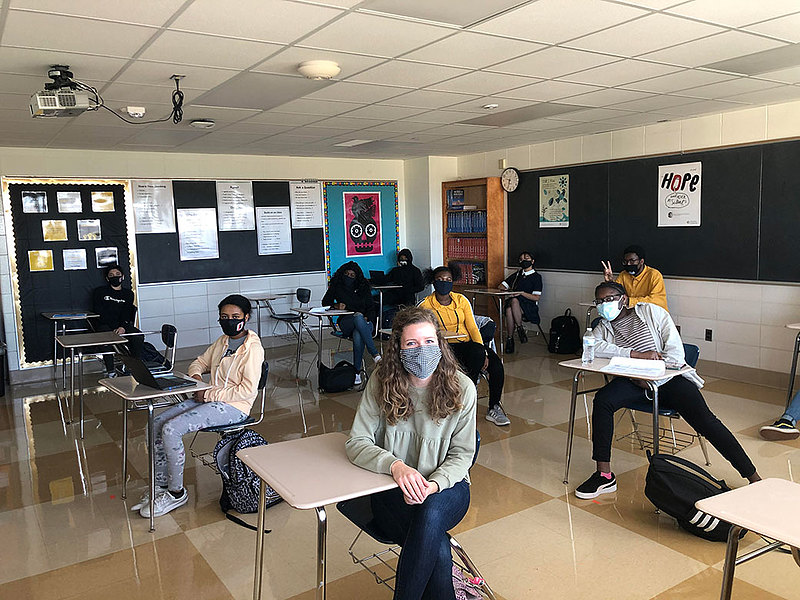

Johanna Beaupre ’18 (center) says, “The best part of teaching is the relationships we build with students. I noticed a major difference in my happiness level when we were back in person this fall and could finally have that real human connection.”

Has the pandemic underscored equity or access issues in your district?

This pandemic has brought to light many equity issues in the classroom. Most teachers I work with have been aware of these disparities for years, but now the general public is seeing them more clearly. It has been both frustrating and hopeful to watch our country realize all the social supports that schools provide our communities, from food security to mental health resources. While I’m glad that more people are seeing the value in public schools, this has also come with a lot of animosity toward the school system for not being able to provide a typical year. Being called a hero in March and then lazy and selfish in August (for being concerned about our students’ and our own safety) has taken a toll on many teachers.

What has helped you navigate this time?

My EL team has implemented the use of an app called TalkingPoints to communicate with families. It allows teachers and families to send text messages back and forth that automatically get translated into each other’s preferred language. It also allows us to connect with more families since not every family has access to email.

Jess (Jewell) Tangen ’08

Physical and health education teacher at St. Benedict School in Decorah, Iowa

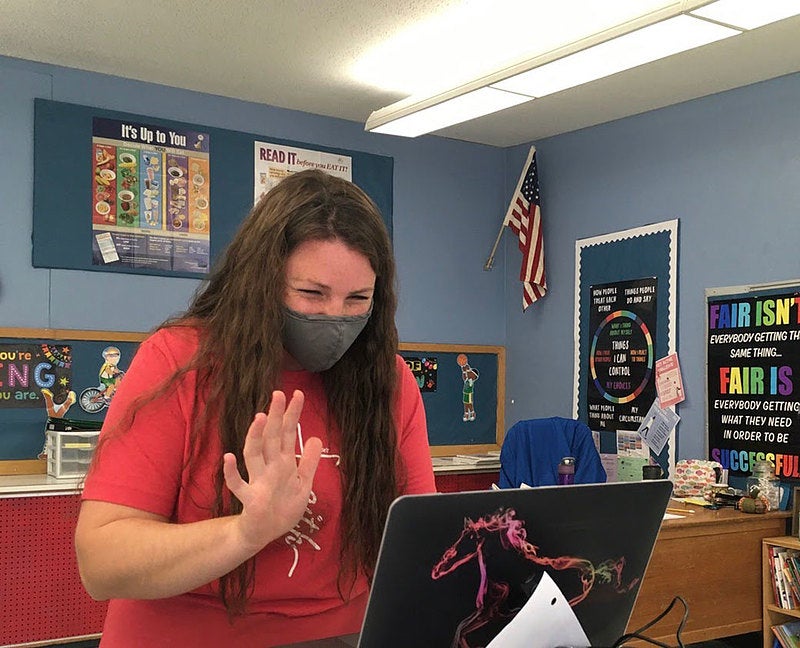

Jess (Jewell) Tangen ’08

How is your workload different from a typical year?

This year I’ve had to change activities up so that students can be spaced out. I’ve had to think about equipment use and cleaning equipment more often. We’ve tried to stay outside as long as possible so kids can take mask breaks! I’ve also tried to make sure my health lessons are written up and available on Google Classroom for middle school students in case any have to be out on quarantine. If they’re able, I want them to follow along at home while on a Google Meet and stay involved as much as possible. It has definitely taken longer to prepare for each day.

Are there any positives to teaching this way?

I have learned a lot more about technology, and I will continue to grow and learn professionally. I want to have a lifelong impact on my students, so I will keep learning new ways to connect with each of them whether we are in masks, in school, or out of school.

Lindsey Ahlers ’18

Special education teacher at Fernbrook Elementary in Maple Grove, Minn.

Lindsey Ahlers ’18

In a typical year, what do you love about teaching?

I adore working with students and building connections with their families. Working with students with all ranges of abilities has taught me so much. I have learned patience, compassion, and understanding. I love figuring out the “puzzle piece” for what works best for them and seeing how they think.

What challenges have you faced during COVID?

As a special education teacher, the majority of my students learn best using various instructional strategies such as multisensory approaches and engaging with the material hands-on. Providing meaningful learning opportunities for my students with multimodal approaches has been a great challenge.

Another area of difficulty has been in teaching social skills. This is much harder to do virtually. However, my students are learning digital citizenship and Google Meet norms while still working on conversational, turn-taking, and self-advocacy skills.

Erik Mandsager ’20

English teacher at Jordan High School in Sandy, Utah

Erik Mandsager ’20

What has helped you navigate this time?

One of the great joys of this year has been seeing my students welcome each other. Many students have transferred into my class later in the year because their family was impressed with how our school handled COVID-19 or because they tried online learning and it didn’t work out. Recently, one of my students noticed we had a few new students and requested that we redo the name game we did at the beginning of the year so we can all get to know each other.

Do you think COVID will permanently affect how we teach and learn in the future?

I predict online schooling will always be an option and teachers will be expected to put everything online now. This is not necessarily a negative thing though. When all students have an online option, students can keep their families safe, arrange their schooling around their work schedule, and take care of family members. I just hope that in-person schooling doesn’t become a luxury like higher education largely is. Every young person should have the right to make friends and learn skills in person regardless of their socioeconomic class and the health of their family.

Kerry (Kramer) Johnson ’83

Retired from teaching at North Winneshiek School and in the Decorah School District, Iowa; assists two children with online learning

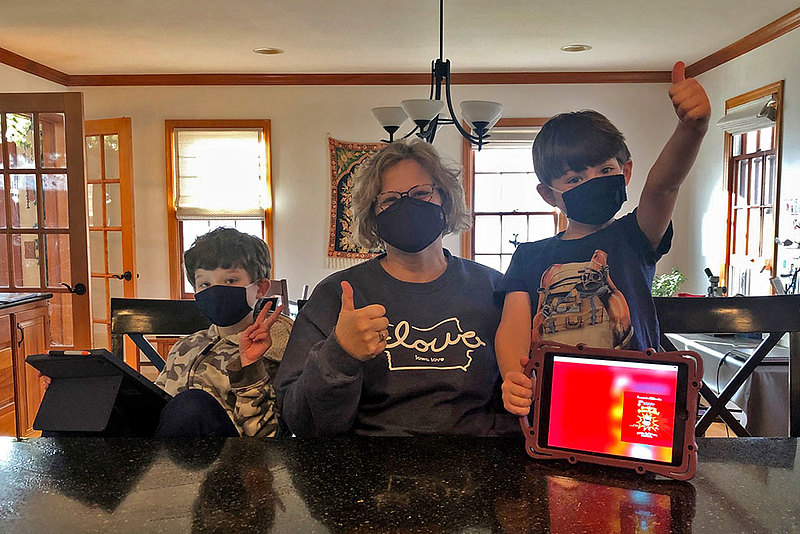

Though retired from the traditional classroom, Kerry (Kramer) Johnson ’83 assists a five-year-old and a ten-year-old with online learning two mornings a week.

Do you observe any specific COVID safety protocols while you teach?

The children and I wear masks during our entire time together. When the weather was nice, we worked outside on the deck. When we work inside, some windows are open to allow in fresh air.

What feels good about being able to teach in this way?

I love being able to help a family who isn’t comfortable having their children attend school in person. I wasn’t comfortable subbing in the school this year, partly due to my age, as well as keeping my contact with others at a minimum. So I enjoy being able to teach, but not in the school setting.

Laura Fuller Russella ’10

English teacher at Middleton (Wis.) High School

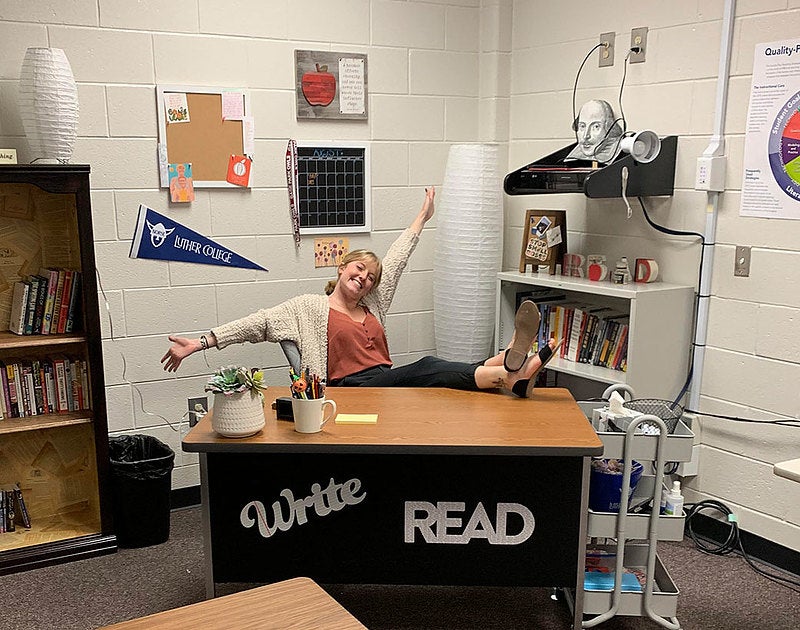

Laura Fuller Russella ’10

How is your workload different from a typical year?

Everything I used to be able to do on the fly is suddenly an unfamiliar multistep process. I don’t think that’s unique to teachers—a lot of people are working remotely—and I don’t think it’s necessarily bad that we’re rethinking a lot of what we’ve been doing. We’re collaborating more, redesigning curriculum, refocusing our lessons and assessments—that’s good, important work! But it’s essentially like every teacher is brand-new to the job.

What challenges have you faced during COVID?

It’s often an invisible part of high school English that students rely on their teachers in a much more human way than they do teachers in other subjects. We see their writing and work with them on communicating, we read stories of people struggling, and it just sort of happens that English teachers hold steady a basin of students’ painful experiences, their fraught relationships, their tenderest new ideas.

That basin isn’t so full this year, and I don’t believe it’s because students are somehow not struggling. Older students, especially those I’ve taught before, are a bit more willing to seek me out to say that they need some support. My freshmen have only seen me on Zoom—they have no proof that I even have ankles!—so I don’t have that rapport yet. I’m working on relationship-building, but it’s hard. For technological reasons or reasons of general teen-aged shyness, they rarely turn on their cameras during Zoom classes, so many of them remain people whose work I’ve read but whose faces I’ve never seen. If they’re in crisis, I usually would know by this time of year. This year: radio silence. I’m most worried about kids suffering in silence, feeling isolated and not knowing they have a boisterous but very caring English teacher who would be honored to walk with them through whatever sticky situation they’re in.

Nothing is going perfectly in my classes, but it’s clear that welcoming kids—again and again, in new ways all the time—is my most important work this year.

Becky McCammon ’98

Restorative practices program coordinator, St. Paul, Minn., public schools

Becky McCammon ’98 (in the black cardigan) with fellow restorative community members at the East Side Freedom Library in St. Paul, Minn.

McCammon, who taught in the classroom for 14 years, now helps implement a cultural shift in the St. Paul public schools by introducing restorative practices. She describes them as a contemporary rendering of indigenous practices in which people gather in a circle and use a talking piece; some of us might recognize this as circle practice.

More broadly, she says, restorative practice is the belief that we learn most profoundly through relationships and that we’re most accountable to healthy relationships. The program came about in St. Paul because the local educators’ union bargained for it, originally as a way to healthily address times when people are in pain or might be looking for language to express their needs. “It turns out that suspensions and expulsion and punishing language doesn›t serve us to become dynamic learners or to feel good in school and in ourselves,” she says.

McCammon—who published an educator’s guide, Restorative Practices at School, this year and won the 2020 Education Minnesota Human Rights Award—started in her role four years ago, rolling the program out to an initial six schools. In year two, there were nine. In year three, 12. Now, there are 25 or 26. “Yes, my job keeps getting bigger,” she laughs.

The work looks slightly different at different schools, and interestingly, it involves a lot of adults in circle practice exploring, for instance, the language they use to talk about student learning, or their relationships with discipline, power, or race. As some schools have introduced circle practice to their students, they’ve also trained students to be circle keepers.

During the pandemic, St. Paul schools are mostly distance learning, which means that circle practice is virtual. But McCammon points out that this allows people to regulate their comfort differently, which often means that people show up feeling ready and willing to share.

Eventually, as a school builds its restorative practices, McCammon says, it can tackle more challenging ideas and curriculum: “Through healthy relationships, we can take on more rigorous work. Because with an educator who I feel believes me, anything is possible.”

Morgan King ’19

English teacher at Peachtree Ridge High School in Suwanee, Ga.

Morgan King ’19

King knew all her life that she wanted to be a teacher, but she struggled with which subject to teach. “I wasn’t confident as an English student,” she says, “but something about the English classroom got me intrigued. When I got to Luther, the opportunity to explore and push the limits of that curiosity made me so excited to do that in my classroom.”

Now, as a high school English teacher in Georgia’s biggest school district, she takes a broad approach to literature, asking her students to apply critical thinking and analytical skills to podcasts, films, music, and current events. For two semesters, she taught Netflix’s When They See Us, a drama series that revolves around the Central Park Five. “I paired it with The Crucible to talk about the start of our justice system and whether or not we’ve made any headway,” she says. “I went back into the New York Times archives and printed out all the original news articles, and we talked about how language changed in a matter of days—about charged language and how racism is built into media representation.”

When the pandemic hit last spring, it forced King and fellow educators to consider what education really means. “It was such a moment of pure humility for us, that what we do every day is really important, but it’s not about how much content we spew at our students—it’s about whether we are allowing them to feel safe and comfortable in the world that they’re in right now,” she says.

King started turning her students toward more reflective work, like keeping a journal or interviewing a family member about facing adversity—things to help them process current realities and also forge stronger connections outside of the classroom. “I couldn’t create a lesson better than what life is giving us,” she says.

And that’s really at the center of King’s teaching philosophy—engaging fully in life and learning. “I want my students to realize that literature is everything around us all of the time. I want them to realize that they’re doing this analytical work, this critical thinking when they open up Instagram or watch that new Netflix series,” she says. “I want them to be lifelong learners—to go out and see the world and ask questions about it.”

Lauren (Keller) Mortimer ’20

Math teacher at Holly Hill Elementary in Enterprise, Ala.

Lauren (Keller) Mortimer ’20

A month and a half into the school year, Mortimer knew she had to change things up. Except for a 15-minute snack and a 45-minute PE, her sixth-graders spend all day in the same room, even eating lunch there, unable to collaborate or do much group work because of physical distancing precautions. They were antsy and disengaged.

So in spite of the fact that she was a first-year teacher who was still getting to know the curriculum, she decided to try gamification, turning lessons into game-based learning. It was a method she’d seen as a student teacher in Stewartville, Minn. At first it seemed chaotic, but, she says, “The more I saw it unfold, the more I saw exactly what the teachers did with it and how they were pre-teaching and re-teaching and working with individual students. In a class of 48, every single kid was super excited to be learning, and every one of them was working toward a goal they wanted to achieve—it was incredible.”

In her own classroom, Mortimer surveys kids about their interests, then builds a game in Google Slides. Students choose characters that link to exercises or problem sets, and they usually fight a bad guy by completing a challenge at the end. It takes a lot of time to put together, but once Mortimer rolls it out to her students, their learning becomes self-paced and self-directed, which makes her more available to students having trouble.

The feedback from students has been super positive. Mortimer says, “I had one little girl whose dad pulled up the first day for [physically distanced] meet-the-teacher in their car. She asked what I taught, and I said, ‘I teach math.’ Every part of her just slumped. Now that little girl is writing I LOVE MATH in her notebook.”