The Plume Hunter and the Icy Orb

Planetary scientist Ujjwal Raut ’01 joins a NASA mission exploring a moon with the potential for life in our solar system.

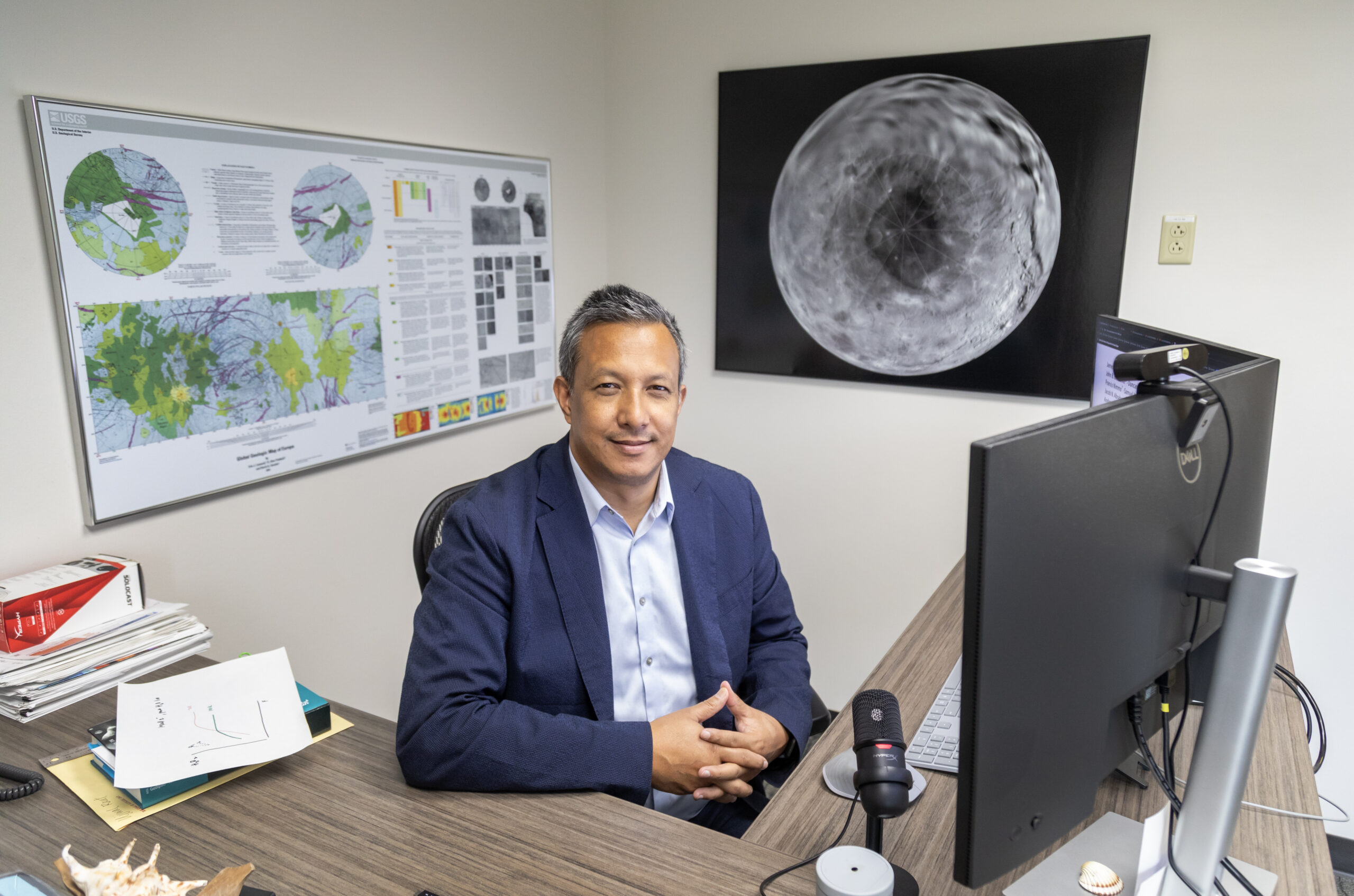

Ujjwal Raut '01 heads his own lab at the Southwest Research Institute, a nonprofit that partners with global governments and industries to conduct research in space physics, planetary science, and astrophysics.

A Lab That Shapes a Life

Ujjwal Raut ’01 could have excelled in a number of fields, but he happened to share a first year at Luther with Jeff Wilkerson, a physics professor newly arrived from UC Berkeley with instruments on loan to set up a research lab for Luther students. This serendipity would turn out to shape Ujjwal’s life.

“We’d be studying thermodynamics, and he’d be so animated and full of energy, with funny anecdotes to share,” Ujjwal recalls. “Physics can be a dry, boring subject, but the way he presented the material was fun and interesting. If it weren’t for Jeff’s mentorship and guidance over those undergraduate years, I probably would have had a change in career.”

In Wilkerson’s lab, Ujjwal investigated whether you could detect gamma ray bursts—very high-energy events in the cosmos—via infrared light. “It was very hands-on, hardware-oriented, experimental work using the instrumentation and equipment Jeff had brought from Berkeley,” Ujjwal says. “It really cemented that this is what I wanted to do in the future.”

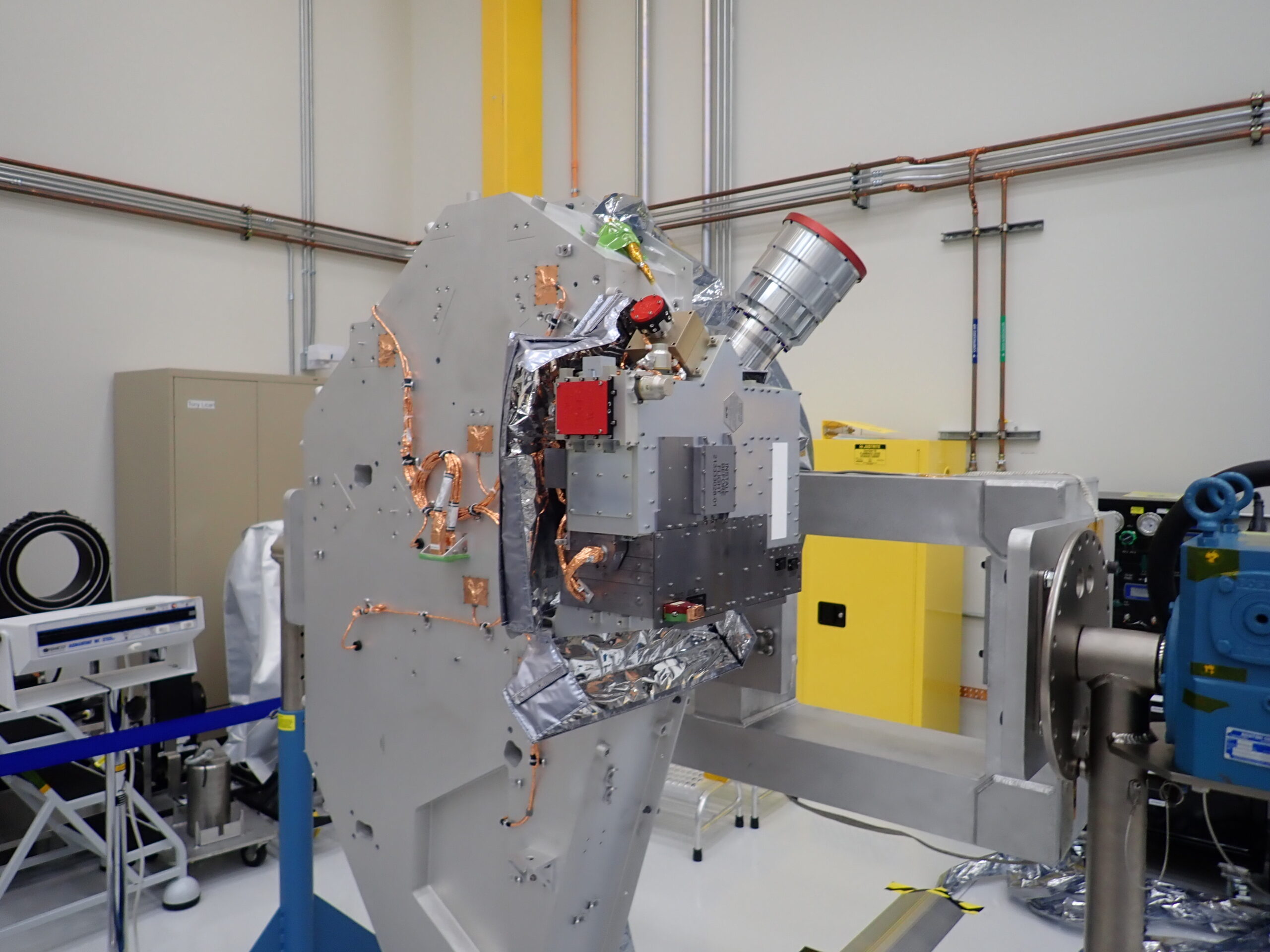

Ujjwal Raut '01 is co-investigator on the ultraviolet spectrograph on board NASA’s Europa Clipper mission.

An Expert on Planetary Surfaces

Ujjwal earned a PhD in engineering physics at the University of Virginia (UVa) during a time when planetary science was making great strides. NASA’s Cassini mission was exploring Saturn, finding methane lakes on Titan and plumes erupting from its tiny moon, Enceladus, reminiscent of Yellowstone’s geysers. After a postdoc stint at UVa, Ujjwal moved to San Antonio, Texas, to start his own lab at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), a nonprofit that partners with global governments and industries to conduct research in space physics, planetary science, and astrophysics.

SwRI has had a hand in many high-profile missions, including Cassini, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mapping the moon, the European Space Agency’s Juice mission to Jupiter’s icy moons, the New Horizons mission exploring Pluto and the outer edges of our solar system—the list is long.

Ujjwal’s lab at SwRI specializes in investigating planetary surfaces. He was a co-investigator of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission and a science team member of the Juice mission to the Jovian system. When it came time to launch a mission to study Europa, Jupiter’s icy moon with potential conditions to support life, NASA reached out to Ujjwal.

Europa Clipper’s ultraviolet spectrograph

The Plume Hunter

NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, a space probe launched in October 2024, aims to help us better understand this unique moon. One of the four brightest moons of Jupiter, Europa is a really compelling celestial body because it likely has three qualities essential to life:

- organic compounds

- a liquid ocean—even if it’s covered by a 20- to 25-kilometer-thick sheet of ice

- a heat/energy source—the friction produced as Europa flexes from the gravity of Jupiter and passing moons, which could lead to volcanoes heating the ocean from below

Ujjwal’s role on the mission is co-investigator on the ultraviolet spectrograph (UVS), one of the two instruments on board Clipper that SwRI built. “We like to call the UVS the plume hunter,” Ujjwal says, because when the Hubble Space Telescope was studying Europa using UV in 2012–14, it observed what looked like geysers—water vapor signatures that extended about 100 kilometers above the surface.

This means that Clipper may be able to fly through the plumes and directly sample the oceanic material, otherwise inaccessible beneath 20–25 kilometers of icy crust.

Ujjwal explains, “UVS is like a small Hubble that we’ve put on the Clipper spacecraft, but it gives us a much closer flyby. You can go from thousands of kilometers in orbit all the way down to about 25 kilometers above the surface of Europa. And when we’re having that encounter, we’re looking for these plumes erupting. If they’re made of water vapor, when those water vapor molecules interact with Jupiter’s plasma, they’ll get excited and emit wavelengths that are easily picked up by the UV spectrograph that we’ve built. So the idea is to find and characterize the nature of these putative plumes of Europa.”

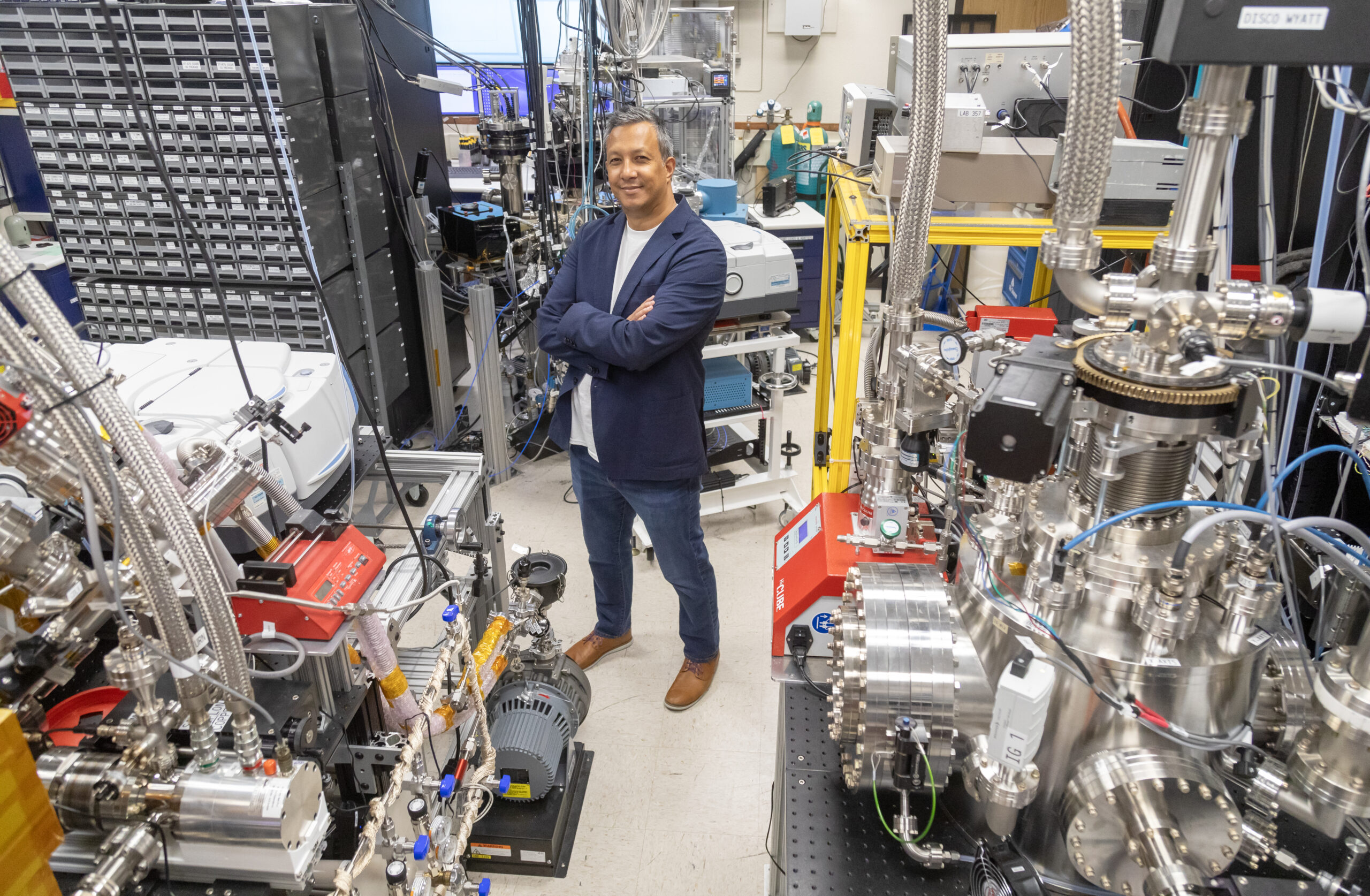

Before Clipper even samples these plumes, Ujjwal and his team will already have run many analog experiments in his lab that simulate possible conditions on Europa. As the measurements from the mission are transmitted back to Earth, they’ll have a rich trove of data from the lab to draw on to interpret those measurements.

Clipper should reach Mars this February and Jupiter in 2030. After completing 49 close flybys of Europa and following extended campaigns, the spacecraft is perhaps bound for a cataclysmic end, with a planned crash into Ganymede, another of Jupiter’s moons. But even this, Ujjwal says, may offer scientific insight. Because Juice will also be studying Jupiter at that time, it will be able to investigate the ejecta that the planned crash kicks up.

In October, Ujjwal and his family attended the Europa Clipper launch at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Ujjwal used two of his limited launch tickets to invite Jeff Wilkerson, who was a critical mentor for Ujjwal, and his spouse, Luther religion professor Kristin Swanson. Unfortunately, Hurricane Milton interfered with Jeff and Kristin’s travel plans, but the launch on October 14 was a huge success.

Becoming Bigger than Yourself

During the daily work of precise instrumentation and measurements, Ujjwal admits that it’s hard to keep the big picture in mind. But ultimately, he says, “Exploring the cosmos and trying to understand what’s out there eventually comes back to answering the bigger questions of who we are and where we come from. Those are grand questions, really big questions. They’re not something you can answer in a lifetime or even multiple generations.”

So part of his life’s work is as a physics professor at the University of Texas, training the next generation of scientists to take up this mantle. “Looking back,” Ujjwal says, “I was really lucky I arrived at Luther the same year that Jeff did. He was a wonderful mentor to me—he convinced me that physics is a worthy profession. I try to communicate that to my students. Through research, they make a small contribution that adds to the bigger picture. They become part of something bigger than themselves.”