The ASAA Turns 40

In February, Luther’s Asian Students and Allies Association (ASAA) celebrated its 40th anniversary. Over its four decades, it has reflected the cultural and demographic shifts of a dynamically changing Asian and Asian American student body at Luther.

As the anniversary approached, Brian Caton, professor of history and former ASAA faculty advisor, grew increasingly aware that little formal documentation existed about the history of Asian and Asian American students at Luther. He set out—with the help of Mia Suzuki ’24— to change that. What follows is a CliffsNotes version of what they learned.

The history that follows is a condensed version of Brian Caton’s lecture, “Recovering the History of Asian and Asian American Students at Luther College,” given in fall 2023.

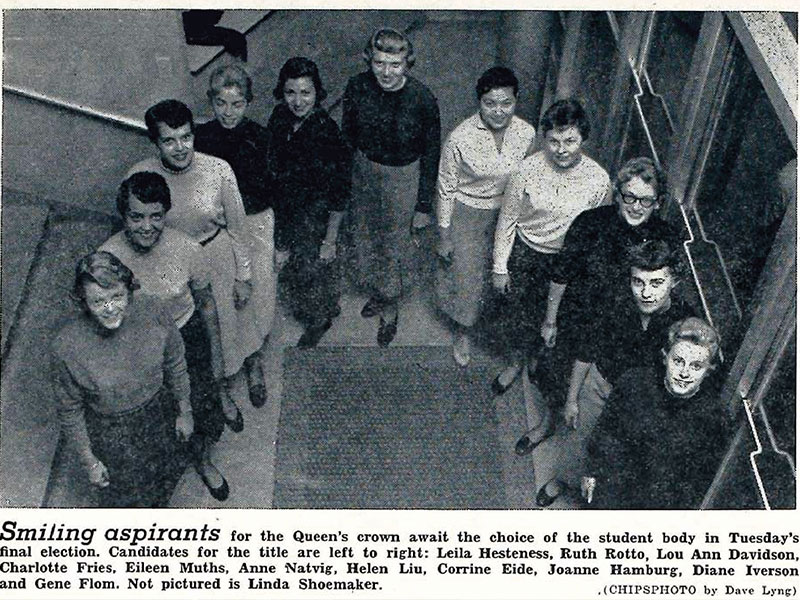

Pioneers of the 1950s and 1960s

Asian students have attended and graduated from Luther since the 1950s. The first was Augustine Chen ’55, a student from China who came to Luther needing just one year of coursework to earn a bachelor’s degree in physics. Also notable was Helen (Liu) Ott ’58, from Taiwan, who hoped to become a pediatrician. Importantly, she was elected homecoming queen in 1957, the first woman of color to hold that office.

In the early 1960s, President Farwell famously pushed the college to increase its racial and ethnic diversity, first through initiating an exchange program with three historically Black colleges and universities, and second through building a recruitment program in urban Chicago. While these measures were aimed toward recruitment of African American students, they sometimes also attracted other students as well—like Susan (Yung) Maul ’69, the first Asian American student at Luther. She happened to be at a Chicago recruitment fair where Luther staffers were hoping to attract Black applicants.

As an Asian American at Luther, Maul was an anomaly. Luther attracted very few Asian American students before 1980—probably fewer than five in that entire time period.

Refugee and Displaced Students of the 1970s and 1980s

In failing to recruit Asian American students, Luther was not particularly unusual in the Midwest. Most Asian American students tended to enroll in colleges and universities near Asian American communities in coastal cities. Luther administrators didn’t anticipate large numbers of such students in their primary four-state recruitment area.

A key change to Luther student demographics in the 1980s came in the form of refugees from Southeast Asia. The first wave of Southeast Asian refugees began to arrive in the US in the late stages of the war in Vietnam in 1975. A trickle of these first-wave refugee students, usually about one or two a year, enrolled at Luther in the late 1970s, including Clara (Phan) Knudson ’79.

The second wave of refugees began arriving in the US around 1978 and 1979, including Hmong people who had aided US forces in Laos during the war. Families and churches in Decorah sponsored about 125 of these refugees by 1980.

Luther sociology professor Kenneth Root saw a key gap in the support services available to refugees: namely, the education of high school students. Services aimed at adults provided language and job training for them, and young children received language and cultural instruction through local public schools. But children of high school age didn’t particularly benefit from either.

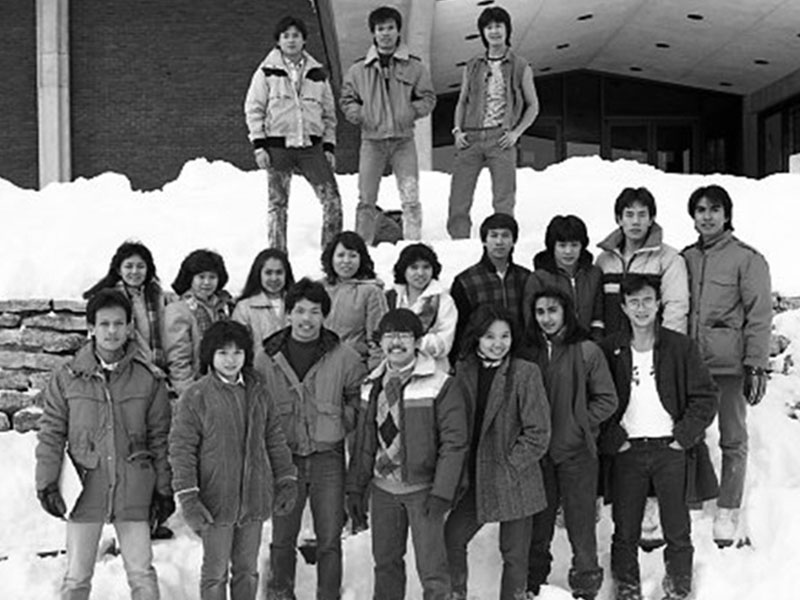

Root and President Farwell secured grant funding to start a degree program for refugee students drawn from across the country. The program balanced a reduced number of Luther academic credits with 11 credits per year of ESL coursework. By the 1983–84 academic year, the number of Southeast Asian students enrolled in this ESL program had risen to about 40.

An ASAA group photo from the 1980s

Founding of the ASA in 1984

These were the students who pushed to form the ASA—the Asian Students Association. There is little documentation giving a direct, clear rationale for why they did so, but the preamble of the ASA’s constitution states that its main objective was to provide “cultural, educational, and social growth for all students—Asian and non-Asian students—of Luther College.” Anyone of Asian origin was welcome to join. The first president of the ASA, N-Tam de Monteiro ’84, insisted in a Chips interview that “We are not going to stick together and alienate ourselves. We want to blend ourselves and learn.”

However, given the time requirements of the ESL program, the additional labor required for learning in an English-language school, and the work-study components of students’ financial aid packages, few members of the ASA likely had time to participate in other organizations and activities that might make them feel more integrated.

An ASAA group photo from the 1980s

Demographic Shifts of the Late 1980s and 1990s

The trend of US citizens adopting children from South Korea, which began during the Korean War, increased in the 1970s, and these Korean American adoptees started to reach college age in the late 1980s. Also in the 1980s, the federal government reduced or eliminated programs established in the 1970s to encourage underrepresented populations, particularly African Americans, to enroll in colleges and universities. This had a pronounced negative effect on the enrollment of African Americans at Luther, which dipped to fewer than 10 students at certain points in the late ’80s and early ’90s.

An ASAA group photo from the 1990s

At the same time, Luther increased its efforts to recruit international students, favoring a strategy of cultivating larger numbers of students from a few countries rather than one or two students from many different countries. In addition, the college adopted a minimum TOEFL score for incoming students, which had the effect of favoring students from countries that had been or still were colonized by Britain or were protectorates of Britain—particularly Bangladesh, Hong Kong, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. So while the end of the ESL program saw dramatically fewer Southeast Asian students at Luther, there was an increase in Asian international students from other countries.

The Evolution of the ASAA

This shift in demographics changed the character of the ASA from something that was organized around a primarily refugee identity to something that was more oriented toward international students and a broader sense of what would be included as Asian students. Simultaneously, members in the 1990s typically had more time to spend on other organizations. Some students attended meetings of the ASA, the Black Student Union, and the International Student Association, and some years these organizations scheduled their meetings consecutively on a single night so that students could attend all three in the same room over the course of a few hours.

The intensive interest among students involved in these various identity-oriented organizations in the 1990s led them to coordinate their advocacy for each other on campus and in the public sphere. It also led non-Asian students to become members of the ASA, which hadn’t been true in the 1980s. In the early 2000s, on the recommendation of Sheila Radford-Hill, then the executive director of the Luther Diversity Center, the ASA added the word “Allies” to its name.

A Changing Student Body in the 2000s

Restrictions on student visas in the aftermath of the 2001 attacks on Washington and New York resulted in a decrease in the overall numbers of international students at Luther and a significant decrease in the numbers of students from South Asian countries. The college responded to this decrease by shifting its recruitment strategy to the opposite of what it mostly recommended in the 1980s, and Luther went from focusing on a few countries to recruiting small numbers of students from many different countries as a means of guarding against political or economic crisis.

Also in the 2000s, Luther became a partner institution of the Davis United World College Scholars Program, which smoothed financial pathways for international students coming from UWC institutions and increased the number of countries of origin of Luther students.

American students adopted from Asian countries continued to enroll at about the same pace as earlier, with adoptees from China beginning to replace those from South Korea. Second-generation Asian Americans also started to enroll at Luther in recognizable numbers.

While some students from these different demographic groups felt drawn to join the ASAA, others questioned whether they were the sort of Asian the organization sought as members, and elected not to participate.

The ASAA was meant to be an organization that provided support, but even its target demographic felt uncertain about access to that support. Perhaps because of this, Asian and Asian American students increasingly prioritized their participation in athletics, music ensembles, media outlets, Greek organizations, academic clubs, and other kinds of activities.

ASAA membership, then, starting in the late ’90s and particularly in the 2000s, became unpredictable from year to year. Some years there would be six or eight students, other years 15 or 20.

In 2008, the hire of Hongmei Yu as a tenure-line faculty member in Chinese language accelerated the push to create an academic program in Asian studies. The Board of Regents approved an Asian studies minor in May 2013. Subsequently, Yu, as ASAA faculty advisor, encouraged the organization to develop events that could support the Asian studies minor.

The Future of the ASAA

During 2020 and 2021, the Covid-19 pandemic brought the activities of ASAA to a halt. This was especially unfortunate in spring 2021, in the wake of over a year of anti-Asian micro- and macroaggressions nationally and the mass shooting of Asians in the Atlanta suburbs in spring of 2021. During this time, some students felt acutely the need for a student organization that could provide emotional and social support, while other students perhaps obtained the support they needed through other networks, some not tied to Asian identity.

Current Asian and Asian American students certainly continue to face micro- and macroaggressions and other problems on and off campus, and doubtless they want members of the college community to better understand their cultures. But it is not at all clear that they regard ASAA as the means to meet those needs.

Perhaps the narrative of Asian and Asian American student experiences and the ASAA can help current students decide how they want to proceed—whether they want to claim ASAA for themselves and shape it into an organization of support in the 21st century.

Students run tables at Culture Fest 2023 in downtown Decorah.

Student/Faculty Research Makes This History Possible

When Caton put out the call to students to help research this history, international studies major Mia Suzuki ’24 answered. Over the course of summer 2022, the pair interviewed almost 40 alumni about their experiences as Asian and Asian American students at Luther. Suzuki says she learned that “There’s a lot of value in this type of research, where you aren’t just looking through archives or empirical data, but you’re talking to people and then kind of synthesizing their stories. You’re honoring the meaning that they share with you.”

Soon, the interviews will be uploaded into the Luther College Archives so that others can listen to these firsthand experiences.