Scoring a Point for Equity

A Luther education helps launch a lot of trailblazers. But sometimes, Luther welcomes a student who has already made an incredible impact in the world. So it was with Peggy Brenden ’76, who fought, as a high schooler, for the rights of girls to compete in high school sports. Her landmark civil rights case opened up opportunities for young female athletes and fueled the momentum of Title IX.

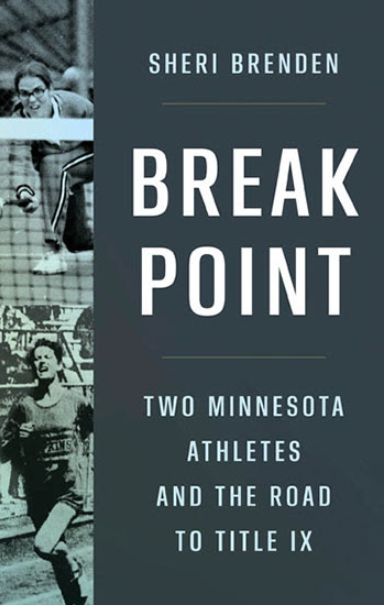

Sheri Brenden ’81, Peggy’s sister, recently published a book about this era in their lives. Break Point: Two Minnesota Athletes and the Road to Title IX is a colorful, engrossing, richly researched chronicle about an episode that’s impacted every female who’s played sports in a school setting in the past 50-plus years.

Peggy Brenden '76 (left) and Sheri Brenden '81 (right) grew up during a time when opportunities for girls to play organized sports were limited.

An Early Love of Sports

The Brenden sisters were raised in St. Cloud, Minn. Peggy says, “We grew up in a neighborhood full of active little boys, so we learned pretty quickly that if we were going to have people to play with, we needed to learn to hit or throw a ball.”

Along the way, Peggy encountered tennis. “I had a competitive fire about tennis from shortly after I was introduced to the sport,” she says. “It fed my need to run and exercise, but also my need to accomplish something and get better at something. It had that blend of something that challenged you both physically and mentally.”

When she entered high school at St. Cloud Tech, Peggy approached the boys’ tennis coach about joining the team (there were no interscholastic girls’ teams). He told her about a rule that prohibited girls from playing at the risk of disqualifying the team from competition, but he offered to let her practice with them when there was an odd number of players.

Peggy was disappointed but dogged—she hit balls against the wall before practice, waiting for boys who didn’t have a partner that day. She spent most of her free time at the courts, including in the summers, hitting against the wall by herself or playing with whomever showed up. She competed in every summer tournament she could, working her way up, in 1971, to a first-place under-18 Minnesota girls ranking by the Northwestern Tennis Association.

Sheri says, “As Peg became a tennis player, she taught me what it looked like to be so passionate about a sport that you would put that type of time into it, work to find people to play against, and choose to put yourself in competitive situations.”

Seeing the passion and dedication that Peggy displayed—and the limited opportunities she had to play competitively—a third sister, Sandy, and her now-husband, Jim Tool, mentioned that the Minnesota Civil Liberties Union (MCLU) had helped in a number of sex discrimination cases.

Peggy tracked down a mailing address and got out her typewriter. She wrote a letter asking the MCLU to legally challenge the rule. Her postscript read “Please hurry. I’m a senior.”

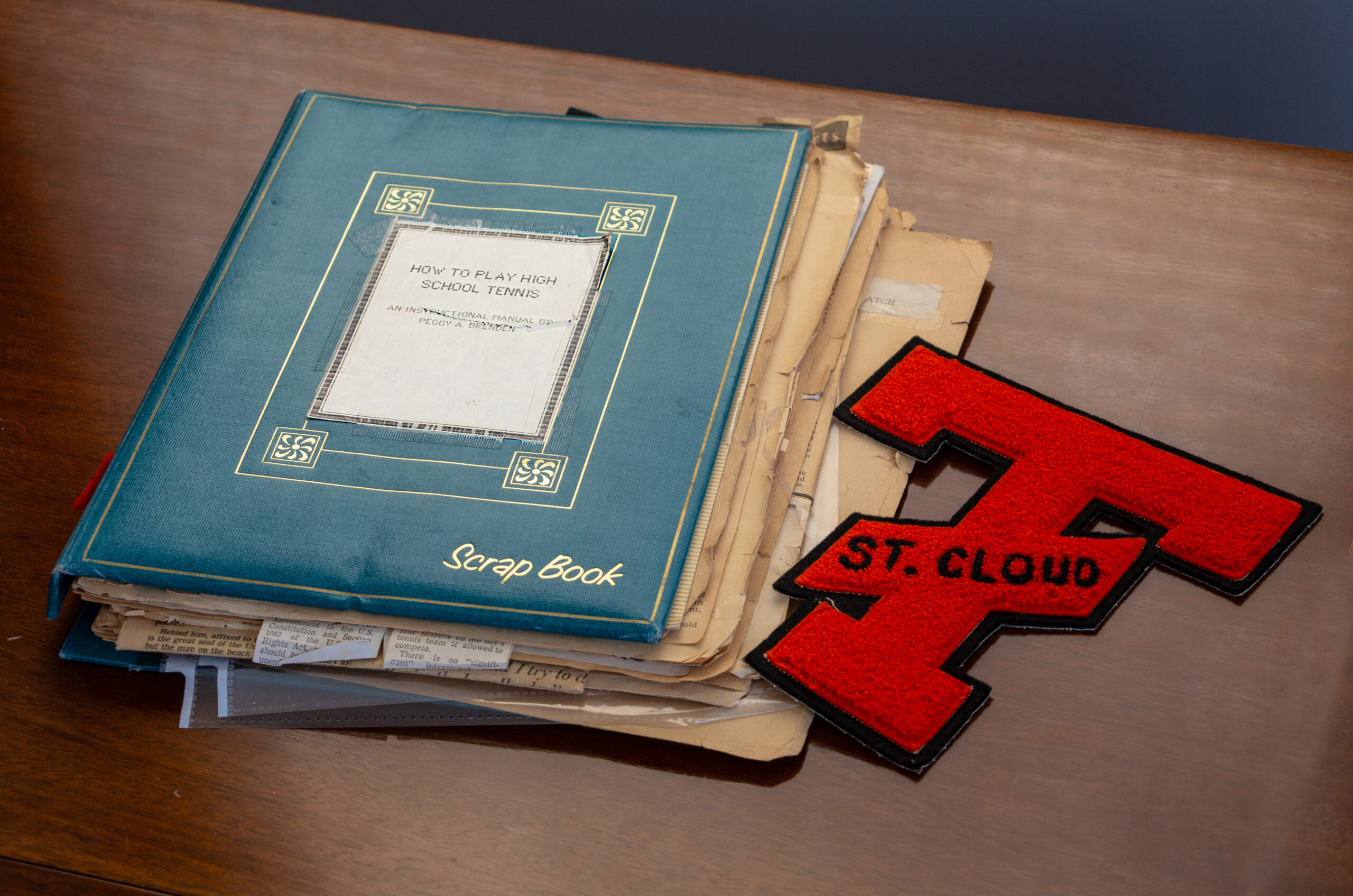

Peggy Brenden '76 kept a scrapbook of her experience fighting to play organized sports in high school.

In the Courts

The MCLU decided to take Peggy’s case, eventually adding a second plaintiff to it, Toni St. Pierre, a cross-country runner and skier from Hopkins, Minn.

In Break Point, Sheri writes that the MCLU attorney who took the case, Thomas Wexler, “believed that winning this case would create a chink in the armor of the high school athletic system built with boys in mind. It would provide the impetus necessary to push high schools, and the Minnesota High School League, to develop opportunities for girls so they wouldn’t be confronted with similar challenges.”

In our digital age of 24-hour news cycles and robust social media, it’s strange to learn that the case took place in a bit of a vacuum from the perspective of the average citizen. Peggy and Toni each spent a day testifying in court—never meeting each other—and the Brendens largely followed the case through the newspaper headlines—when the newspaper covered it. In interviewing former St. Cloud Tech boys’ team tennis players, Sheri realized that they weren’t even aware of the case at the time.

Peggy remembers her own first inkling of the case’s significance—beyond letting her play tennis her senior year—when she came home one day to a copy of the St. Cloud Daily Times. The front page read: “Brenden Sues School District.”

“Things don’t make the front page of the local newspaper unless there’s a little heft behind them,” she says. “So that made me realize that something bigger was afoot.”

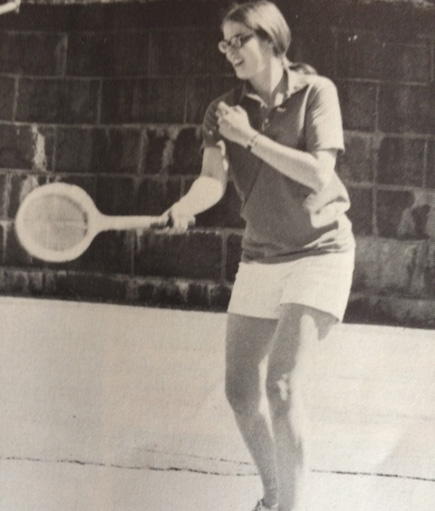

Peggy Brenden '76 spent a lot of time practicing her sport, becoming an accomplished tennis player.

A Landmark Ruling

On April 18, 1972, Judge Miles W. Lord made his ruling: both Peggy and Toni could play on the boys’ teams, and the boys’ teams could not be disqualified. Neither Peggy nor Sheri remembers a press conference, rally, or celebration. “My family—we were good old Norwegian Lutherans,” Peggy says, “so I’m sure we had a conversation at dinner about what this meant and what would happen next, but that was it.”

What it meant most immediately for Peggy is that during her senior year of high school, she played five matches at third singles, winning three, losing two, and earning her high school letter.

The bigger victory, of course, was the opportunity that Brenden v. Independent School District 742 opened up for young female athletes and the momentum the decision gave to Title IX, also decided in 1972.

Sheri makes the point that Title IX legislated equal educational opportunities for women, but that it didn’t specifically address school sports teams or outline how athletic opportunities would be implemented. Peggy’s case made it clear that if schools did not create sport programs for girls and create them soon, they would see lawsuits—and lose them. The year after Peggy’s case, her high school had seven girls’ sports teams.

At Luther, Peggy played first singles tennis, making it into the Athletics Hall of Fame. During law school at the University of Minnesota, she coached tennis at Augsburg College, then at the University of Minnesota. Sheri played several high school sports, as well as Luther tennis and field hockey.

The case shaped Peggy’s life beyond athletics. “I was really impressed with the lawsuit in terms of its outcome, but also because of how it went so quickly,” she says. “The pace of this case is really unprecedented—lawsuits like this usually drag out years. Judge Lord really put the pedal to the metal to make this one happen in a timely way, and the case was an important factor in my deciding to pursue law.” Peggy retired in 2016 after working as a state workers’ compensation judge in Minnesota for 30 years.

Peggy Brenden '76 (center) and Sheri Brenden '81 (right) have spent a lot of time touring Break Point together.

Telling the Story

Over the years, Sheri saw Peggy’s story come up sometimes, for students’ History Day projects or through special awards given by historical societies or halls of fame. But she always felt like its nuance was being lost—that the whole story wasn’t being told. She says, “Even as a family member living with it, I didn’t quite understand how it went and what it meant. It wasn’t a soundbite kind of explanation—it would never be that. It was a special story, it was a significant story, and I was in a unique position to tell it, with both the right skills and the right proximity.”

Sheri was indeed well positioned to tell the story. In addition to majoring in English at Luther, she had served as a Chips editor and went on to work as a reporter for the St. Cloud (Minn.) Times and as research librarian for two of Minnesota’s largest law firms. Her book captures Peggy’s story with honesty, vibrancy, compassion, and fascinating detail.

The sisters have toured the book extensively—including at Decorah’s Dragonfly Books and at Luther—and it resonates with audiences young and old. “There are a number of people Peg’s age and older who express a fair bit of pain or regret, loss, a sense of the absence they felt and the many ways they were blocked from pursuing things,” Sheri says. “They had passions, and their education was different because they were female and they couldn’t always do those things. Those people experienced the kind of loneliness that Peggy probably did as she was going through this. And it’s really meaningful to know that it was shared. That other people felt that pain. You weren’t alone.”

Peggy says, “For a long time, I had regret about not being more outspoken and articulate and, you know, rallying the troops around the cause. You see many young people doing that these days around important social issues. That was not my style.”

She continues, “I’ve come to realize, though, that the way it unfolded for me was maybe another way of reinforcing or inspiring people to do what they didn’t think they could do. It was saying that it can happen anywhere and anyone is capable of it. You don’t have to be from a big city. You don’t have to be a rock star or a world leader. We all have the agency to make a difference. It’s just a matter of doing it.”

Break Point is available at many book retailers, including Dragonfly Books in Decorah and the Luther Book Shop.

Making an Impact on Luther Students

Last April, the Brenden sisters came to Luther to share a meal with English and law and values majors and give a talk about Break Point in the Center for Faith and Life. Here’s what some Luther students had to say:

“I was surprised to learn that someone who went to the same college as me made such an impact in my home state. It was a celebrity moment when I realized the scale of the work that the Brenden sisters had done for women in athletics. Overall, I greatly admired their desire for change and how they paved the way for female-identifying athletes.” —Gretchen Dwyer ’24, law and values major

“After listening to the Brendens speak of how they were discriminated against because of their gender, I realized how lucky I am to be able to play sports on competitive teams with people who support women in sports. I was impressed by their dedication to the cause and how brave Peggy was to fight for equal opportunities at a young age.” —Abigail Ostermann ’26, exercise science and Spanish major, tennis player

“The Break Point presentation reminded me that while we’ve made a lot of progress in allowing women to participate in sports and commending them for their success, we still have a long way to go. Women’s sports are still not treated equally across all levels of competition despite Title IX, and while recent attention on Caitlin Clark has shifted the perception of women’s basketball, there are still a ton of other women’s sports that aren’t receiving the attention they deserve.” —Peter Heryla ’24, communication studies major, tennis player

“I was moved by the level of detailed journalistic work that it took to write about this case. It’s in the details that stories become real for us as readers. As a Chips writer, I can see the influences that writing for the Luther newspaper had on Sheri, how it’s shaped her own style and mind as a writer, thinker, and researcher.” —Ethan Kober ’24, English and religion major