Good Stewards

It’s no surprise that Luther, with sustainability as a cornerstone of its mission, turns out graduates who care about pristine natural spaces. Some of them even commit their careers to maintaining these spaces for the enjoyment of all. During the pandemic, with outdoor recreation more valued than ever, our shared public lands have seen a huge increase in use. We check in here with some alumni who’ve dedicated their lives to stewardship of public lands, making sure these places remain accessible, healthy, and safe.

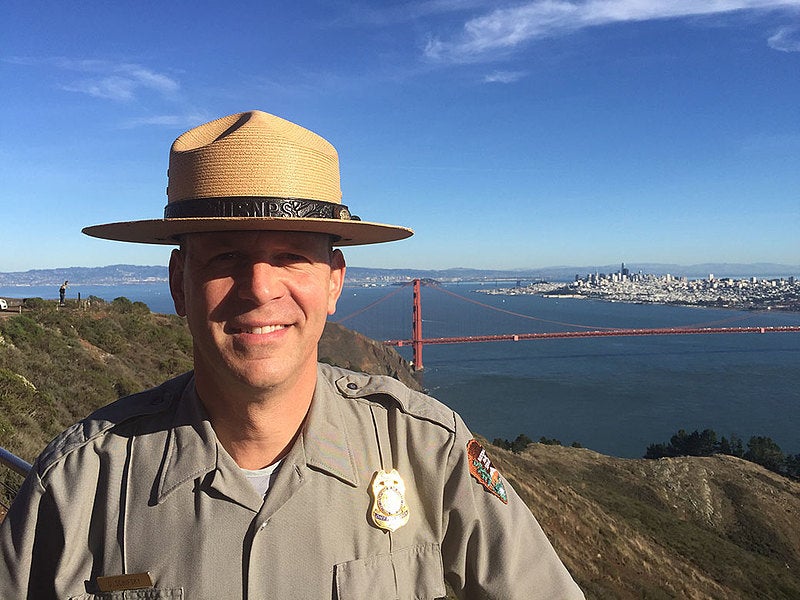

David Schifsky ’93, deputy superintendent of Golden Gate National Recreation Area

About GOGA, deputy superintendent David Schifsky '93 says, "Parks like this are a like a small (or medium) city complete with administrative services and businesses. When I show visitors around the park and point out the diversity of what we steward, they’re amazed."

When did you realize you wanted a career in parks?

When I graduated from Luther in 1993, I didn’t know how great of a fit park/public lands management would be, but I had a hunch. As part of a class project, I interviewed a park ranger at nearby Effigy Mounds National Monument and became interested in natural and cultural preservation. This interest, of course, was fueled by the community/public service values instilled through Luther culture. When I entered the Student Conservation Association (SCA) program as a volunteer in 1994, in Canyonlands National Park, it all made sense. I became a seasonal park ranger for the National Park Service (NPS) and made a fantastic career out of protecting and conserving national parks across the country.

What makes your park special?

I currently serve as the deputy superintendent of Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GOGA), which includes Muir Woods National Monument and Fort Point National Historic Site. GOGA spans three Bay Area, California, counties and was the third most visited unit of the NPS with over 13 million visitors in 2021. It’s an urban park yet home to the most threatened and endangered species (38) in the continental United States. Its coastline, beaches, old-growth redwood forests, and historic buildings are unique.

What’s fulfilling about your job?

Being part of the stewardship of unique landscapes, wildlife, cultural and historic sites, and American stories is humbling. These places are conserved for those not yet born.

Schifsky says, "GOGA is known nationally for its partnerships and innovation. I spend a lot of time building relationships, supporting employees, and working closely with local, state, and federal partners."

Have you handled any dramatic situations?

Many. I worked as a law enforcement park ranger, including rising to level of chief park ranger, for more than 22 years in seven different parks across the country. NPS park rangers do it all. I’ve made arrests, rescued people, saved lives, and worked all manner of disasters or large-scale special events. There have been tragic and challenging incidents I’ve been part of and some powerful saves: while working in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, I was part of a search for a young boy who wandered away from his family’s campsite. Many of us responding rangers had seen similar incidents end tragically, so we were anxious. As I turned a patrol boat into a side canyon of Lake Powell, there he was on top of the rock. My heart leapt: we found him!

If I visit your park, what should I be sure not to miss?

There are so many great sites throughout GOGA: Muir Woods, Fort Point, Alcatraz, any of the beaches are inspiring. The shoreline is alive, bird watching abundant, and wildlife sightings, especially out to sea, regular. If you’re into history, the park is filled with historic military buildings, forts, and layers of the past. All of the services one would want to ensure a safe and comfortable visit are nearby: GOGA is not nearly as remote as many other units of the NPS. Any part of the park will inspire great photos! It’s a world-class park.

Nicole Engdahl ’94, senior vice president of planned and annual giving, National Park Foundation

Nicole Engdahl '94, senior vice president of planned and annual giving for the National Park Foundation, in Glacier National Park

Many people assume that national parks are fully funded by the government. How and why does the National Park Foundation enter the picture?

The National Park Service was created in 1916. As the number of park sites grew, Congress could foresee that the government would not be able to fully fund all the park programs and projects without help from private funding. In 1967, Congress created the National Park Foundation to become the official nonprofit partner of the National Park Service. For more than 50 years, the foundation has raised money to fund grants used to support programs and projects within the parks that help protect and enhance national parks for present and future generations.

With the uptick in park visitors during the pandemic, how has your work changed?

Due to the uptick in visitation and appreciation of the parks, our fundraising also increased significantly. I oversee three programs at the foundation, and all three programs set new fundraising records over the past two years, so we were extremely busy. We had to constantly adapt our strategies in order to be nimble to the ever-changing news as well as the various shutdown and supply chain issues. It was a challenge, but it also gave the staff a renewed purpose for how vital the parks are to our everyday lives.

Engdahl in Grand Teton National Park

What’s your favorite park to get your nature fix?

Picking a favorite park is tough. Each park leaves a lasting impression, and I have truly loved something about every park I have visited. Like many people, during the pandemic, I found solace in the national parks closest to me. I am lucky I live in DC and have many national park sites nearby. I love running on the National Mall early in the morning as the sun comes up over the monuments before the tourists arrive. There is something peaceful and reflective in being among those beautiful structures in the early morning light. Also, I have come to cherish my walks with friends through Rock Creek National Park. It runs through the middle of the city and is such a haven. Being surrounded by all that greenery in the middle of a big city along with the sounds of the creek and the birds immediately soothes my soul. It has been my go-to almost every weekend these past two years, and it has done wonders for my mental and physical health.

Bob Palmer ’91, deputy regional chief ranger for the Pacific West Region of the NPS

What does your job entail?

I’ve worked in a few parks (14 +/-) in every region of the country (except Alaska) and also worked for several years as a ranger in New Zealand. I’m now based in a regional office in San Francisco, and I oversee and serve as a staff expert for a variety of Visitor and Resource Protection Programs (law enforcement, search and rescue, emergency medical services) for the 60 NPS sites within the eight states of California, Hawai’i, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, portions of Arizona and Montana, and the territories of Guam, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands.

Bob Palmer, deputy regional chief ranger for the Pacific West Region of the NPS, has worked in every region of the country (except Alaska) and as a ranger in New Zealand. "They all are special for their own reasons," he says, "and each can offer moments of physical, emotional, or intellectual serendipity." Here, he mans a gate during one of many government shutdowns. Photo courtesy of the Telegraph Herald.

What’s fulfilling about your job?

Over time, I’ve become a go-to person for the NPS with respect to the application of a number of laws relating to cultural and natural resources. I feel most fulfilled when I can help a park and its tribal partners work through difficult issues and find a resolution that meets the needs of park resources and the tribal partners. It doesn’t always turn out great, but when it does, I feel like I’ve earned my pay!

Tell us about some parts of your job the public wouldn’t expect.

This is a great question to which the answer would depend on what aspect of the public is asking the question. By way of example, when there’s an earthquake in Alaska, Japan, or somewhere on the Pacific Rim, our phones ring and we jump into action to respond to a potential tsunami that could impact one of our Pacific parks (or the West Coast of the mainland). Things like this actually happen more often than you might think, and besides tsunamis, we deal with wildland fires, hurricanes, floods, political protests, and public land disputes. It makes you realize the importance of planning and preparing for significant human events, potentially catastrophic natural events, and anything else under the sun. There is no worse feeling of helplessness than when something unexpected is happening, and your confidence of adequate pre-event prep work is low.

In some larger parks that have significant lodging and camping, managing the park and public can be a bit like running a town of 8,000–10,000 residents. The parks become really interesting and dynamic communities that, in a social context, can change significantly from season to season, as well as from weekday to weekend. A ranger can go from working a natural resource protection issue to something more urban in a matter of minutes.

Palmer sailing with his family in San Francisco Bay on the NPS-owned historic vessel Alma while assigned as the acting superintendent of San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park in 2019

Have you handled any dramatic situations?

If you stick around in any job, you’re bound to brush up against some form of drama. I’ve been on some pretty big wildfires, have done human rescues/recoveries, as well as quite a few really interesting investigations and work with endangered species, including dealing with beached sperm whales! Without a doubt, the most significant incident that I was ever involved in was an investigation and recovery of the remains of 41+ people who had been stolen from a park collection by a park employee, and the subsequent return of these people to their American Indian descendants. That was simultaneously the most rewarding and troubling work that I was ever a part of.

Andrew White ’11, visitor use management specialist for the central planning office of the National Park Service

When did you realize you wanted a career in parks/public lands?

By a stroke of luck, I interned at Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming during the summer before my senior year at Luther. I got just a taste of some of the complex challenges involved in protecting special places like that—transboundary wildlife, private lands within park boundaries, increasing and changing visitation patterns, human-wildlife conflict. I saw working for the National Park Service as a great way to put my environmental studies degree to use!

Andrew White ’11, visitor use management specialist for the NPS central planning office, says the planning process in his office "tends to be very iterative and collaborative, involving lots of stakeholder and public input and lots of reconsideration. Once we have decisions, I help to write everything up in a plan that makes sense, and complete the environmental compliance as well." Here, White is pictured in Grand Teton National Park, where he worked for six years.

What does your job entail?

I currently work as a visitor use management specialist for the central planning office of the NPS, known as the Denver Service Center. In this capacity, I help park managers at national parks across the country to address challenges associated with visitor use. The goal of my work is to develop plans that will ensure that park visitors have meaningful and enjoyable visits to their parks, while sustaining and protecting the parks’ resources (scenery, wildlife, vegetation, archeology, historic buildings, soundscapes, etc.). Prior to my current role, I worked at Grand Teton National Park for six years doing interpretation (frontline interaction with park visitors), administration, and public affairs.

What’s fulfilling about your job?

Planning takes a long time—a typical project usually takes at least a few years to complete. But when you do it right, it can make a lasting and meaningful impact. One recent example has been at Amache, a place in southeast Colorado where Japanese Americans were incarcerated during WWII. Since late 2019, I’ve been a part of a team that has been evaluating whether it would make a good addition to the national park system. In March, President Biden signed the Amache National Historic Site Act, making it the newest addition to the park system. While the law is a somewhat indirect result of our work, it’s super rewarding knowing that our study will guide early management of a new national park site, and that this place is now preserved in perpetuity so that future generations can see what remains of one of the darker chapters in American history.

White says, "One thing I love about my job is that I get to work on projects at fascinating parks across the country. At any given time, I might be working for 12–15 different national parks. I’ve learned that each park is special in its own unique way. Some things you would expect—the incredible scenery of Kenai Fjords or Glacier come as no surprise, and the interplay of wind and light at places like Great Sand Dunes and White Sands could also be expected. However, I’ve found tremendous satisfaction learning about places like Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area in Atlanta—a little-known national park that serves as this tremendous oasis of nature, recreation, and cooler temperatures for millions of people in the heart of a steamy metropolitan area. Canyon de Chelly National Monument is another special place I’ve learned about—it’s a magical place where people have lived for thousands of years, and where Navajo families continue to make their homes, raise livestock, and farm the land." Here, he enjoys a float on the Snake River in Grand Teton National Park in 2018.

Tell us about some parts of your job the public wouldn’t expect.

I think most people would be surprised at the complexity, and oftentimes controversy, that goes into protecting these places and ensuring that people can have an enjoyable visit. I think people would be surprised at how much time we spend wrestling with the right way to identify a visitor capacity for a trail, debating the best way to redistribute use through an area, or thinking about how to make sure our plan is legally defensible and politically palatable.

Any tips to make my park visit a good one?

Plan ahead! It’s a dynamic time to visit national parks. Many parks have recently implemented new reservation systems for campgrounds; specific areas, trails, or roads; or for park entrance altogether. Visit the park website before you go to make sure you aren’t caught off guard by any of these. (Despite this being directly related to my line of work, I am one of the worst perpetrators of failing to plan ahead. Don’t be like me!)

Thawdar Zin ’21, restoration technician at Resource Environmental Solutions (Milwaukee branch), which restores public and private lands throughout the country

Thawdar Zin '21 helps restore prairies, streambanks, and woodlands through prescribed burns, seeding, and invasive species removal.

What does your job entail?

Here in the Midwest, major RES projects include woodland restoration, prairie restoration, and streambank restoration through invasive species removal, seeding, planting, and prescribed burning.

What’s rewarding about this work?

I’m reminded that I’m making a difference. Sometimes the results of the job are very immediate. Seeing a beautiful forest recently cleared of invasive species, mostly buckthorns and honeysuckles, is quite satisfying. I have yet to see the result of the prairie restoration we did last year this spring, and I’m quite excited for it. Speaking of prairie, one of the best things about working in prairies during spring and summer is that I get to see a lot of beautiful prairie plants and animals, and knowing that my work contributes to the well-being of these native species of plants, insects, and animals prevails over the laborious nature of work I have to do.

As a restoration technician, Zin works on projects that range from mowing down smaller invasive plants and doing herbicide applications to prescribed burnings.

How is your work shaping how you see the larger world?

My job teaches me the importance of maintaining the integrity of natural places, and how fragile they are! It also teaches me that there aren’t enough resources to prioritize this kind of work even though it is very important. It teaches me that there still need to be changes in a larger political context in order to keep our fragile natural places intact because we can only do so much restoration work, and if there is no major support from lawmakers and changes in policies regarding environmental well-being, most of the job we do will only be in vain.

Beth (Ramsey) Shumate ’97, Parks Division administrator at the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks

Beth (Ramsey) Shumate ’97, Parks Division administrator at the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, works to protect her state's parks and trail systems and keep them accessible to everyone. She says, "Shows like Yellowstone seem to drive the number of people who buy land in Montana so they can live this dream of the wild west. Each and every chunk of land or water access that we can secure in perpetuity is so important right now." Here, she's shown in Wild Horse Island State Park, an island on Flathead Lake where her division preserves bighorn sheep habitat. The island produces some of the world's largest rams on record.

Tell us about your career working for Montana parks.

Growing up on a dairy farm in Minnesota, I spent most of my childhood outside on pasture cow paths and trails through the woods. Serving as a wildland firefighter (on a hotshot crew) brought me to the western part of the US, where I fought fires from the southern border of Arizona to the Washington coastline, and I immediately fell in love with Montana.

I’ve lived all over this amazing state for the past 18 years, including five years in eastern Montana working as a park manager at Hell Creek and in other positions serving Montana’s extremely rural communities. This is not a lifestyle for the faint of heart—there are food deserts, no shopping or supplies, and no social constructs to entertain you or where you can find friends readily. It’s sort of like serving your time so you can then relate to other staff that have lived through the same hardships in our other remote locations.

I’ve worked for Fish, Wildlife, and Parks for 14 years, nine of which were as the state trails administrator, where I worked with just about every community of Montana providing technical assistance for their trails and outdoor recreation projects. I am extremely passionate about outdoor recreation, especially trails and public land access for all. Our parks and trail systems play a vital role in our well-being, especially our overall health, our economy, and in our communities. For the past five years, I have been the Parks Division administrator, and it has been a true honor.

Shumate helps groom West Yellowstone for dogsledders, snowmobilers, and other winter recreation.

If I visit your parks, what should I be sure not to miss?

Definitely visit Wild Horse Island!