A bird in the hand

by Kate Frentzel

The hawk had caught me. It was never the other way around.

—Helen Macdonald, H Is for Hawk

For a few weeks each fall, a handful of Luther interns experience pure magic.

“The awe never really goes away,” says Mary McTeague ’22. “Whenever I handle a hawk, I’m struck by both their beauty and their strength.”

Brynn Olsen ’23, an environmental studies major, agrees. “You’re holding a wild raptor—it never gets old.”

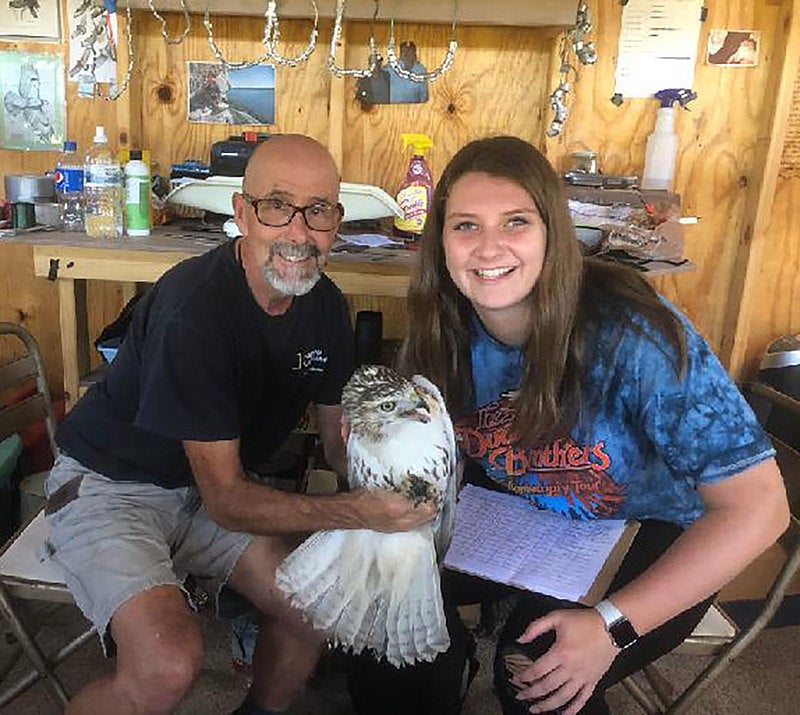

Luther RRP interns, like Brynn Olsen ’23, here displaying a red-tailed hawk, work with local experts to band migrating raptors, growing our body of knowledge about how these birds live and move in a changing world.

McTeague and Olsen are two of six Luther interns employed by the Decorah-based Raptor Resource Project (RRP) to help trap and band raptors as they migrate south each year. Under the guidance of local experts—and from the convenience of a banding station located on Luther’s campus—their work contributes to a larger body of knowledge that tracks bird populations, dispersal, migration, health, life history, and survival rates.

That’s the big picture. On a personal level, these unique internships allow Luther students to leverage local resources and expertise to try out field research, build skills in conservation, and explore possible futures.

A partnership focused on education

Luther has partnered with RRP, founded in 1989 by raptor advocate and educator Bob Anderson, since 2017, when former Luther staffer Emily Neal and RRP’s Dave Kester collaborated to bring a raptor banding station to campus. The Hawk Hill station, funded through RRP and a grant from the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, is situated in the northwest corner of campus on a hilltop prairie peppered with stands of cedar and aspen.

Intern Margaret Mullin ’24 handles a sharp-shinned hawk that will be measured and banded before release.

The vision for the station was for it to focus on education—Kester says that’s why it was built so large, to accommodate entire classes. In its five years of operation, interns at the station have banded hundreds of birds and shared the splendor of live raptors with just as many area students. Luther classes and homeschooled children regularly visit the blind, and Kester will often take a live hawk from the station down to campus to show Luther bio students, or to Decorah schools like John Cline Elementary.

In this way, the Hawk Hill station acts as an incubator for future bird conservationists, whose early encounters with these wild animals will hopefully breed a lifelong interest. This mission resonates with first-year intern Mara Anderson-Skelly ’25, who would love a career in environmental outreach. “Science can only get you so far with connecting with nature,” she says. “It’s essential to experience it firsthand.”

Bird banding with local experts

In the Western Hemisphere, researchers from Canada to South America work together to understand bird populations, and one way they do this is through banding—carefully trapping wild birds, recording information about them, then attaching a metal band with a unique serial number around their legs. In the US, these bands are issued by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). When a banded bird is recaptured or found dead or injured, the USGS and the researchers who applied the band are informed.

At the Hawk Hill station, the bands are part of the inventory assigned to Kester, master bander permit holder, member of RRP’s board of directors, and mentor to Luther RRP interns. Kester has been handling wild raptors since 1997, having learned the art from renowned researcher Jon Stravers.

“I just love to handle hawks,” Kester says. “They’re everywhere around us, they’re common, but most people don’t know anything about them. I just fell in love with them.”

RRP’s Dave Kester, a master bander permit holder and member of RRP’s board of directors, mentors Luther students—like biology major Emily Martinson ’22—as they learn critical conservation skills.

The setup at the Hawk Hill station typically includes three nets—a bow net, a dho gazza net, and a mist net—and multiple lures to attract raptors. Kester trains interns on how to work the traps, collect hawks from the nets, and take a variety of measurements from weight to wing cord to tail length, all in a way that is safe for both bird and handler. The interns choose a band from a variety of sizes designed to fit everything from a petite sharp-shinned hawk to a 15-pound eagle (eagles aren’t trapped intentionally, but they’re banded when they’re caught inadvertently) and fit it around the raptor’s leg. Under that band’s unique serial number, interns record the data they measured and release the bird.

While the Hawk Hill station is a stellar education outpost, RRP has a second banding station where Luther interns really hit the research jackpot. It’s on 500 acres of private land in the bluffs above the village of Wyalusing, Wisconsin, just south of where the Wisconsin River joins the Mississippi. Since the Mississippi River is the fourth-largest flyway in the country, this banding station is an exceptionally productive spot. Students at the Wyalusing station work under master bander Stravers.

With only about 2,000 master banders in the US, Luther students are lucky to have access to local experts like Kester and Stravers and the mentorship they offer. Olsen, who hopes to work in raptor research longer-term, says, “It’s nice to have people behind me who know areas that I might be able to go into. I’ve been very fortunate to work with Dave and Jon—they’ve taught me a lot.”

First-year intern Mara Anderson-Skelly ’25, who'd love a career in environmental outreach, releases a red-tailed hawk.

“This partnership between Luther and RRP is truly a win-win,” says Jon Jensen, professor of philosophy and environmental science and director of Luther’s Center for Sustainable Communities. “RRP gets a prime location for their banding station and Luther benefits from having the station on campus and having easy access to wildlife experts. Our location in the Driftless area and our 800-acre campus in the river valley are such assets for Luther, and it’s a bonus when we’re able to leverage them in this way.”

Up close and personal with wild raptors

Handling a wild raptor for the first time is a standout moment for most interns. Anderson-Skelly remembers being instructed to sit down while Kester brought her a catch. “It was like the first time someone let me hold their baby,” she laughs.

McTeague says, “I was so excited to catch my first bird, but there were also some nerves involved when I realized that I was about to handle a very powerful wild animal.”

“Handling the birds is the highlight of this job,” says first-year intern Owen Matzek ’25. “Studying their features up close and distinguishing species is really something you have to experience to understand.”

Luther’s six RRP interns aren’t the only ones who experience this. Luther environmental studies classes regularly take field trips to the station. “When I take students to the banding station,” Jensen says, “I can see the spark in their eyes as they are up close with these powerful birds and feel the excitement of applied research.”

“Whenever I handle a hawk, I’m struck by both their beauty and their strength,” RRP intern Mary McTeague ’22 says.

Paul Skrade ’04, associate professor of biology at Upper Iowa University, has two students interning at the Hawk Hill station and also takes his wildlife management classes there for field trips. He says, “A student seeing a raptor up close and personal (and for some, getting the chance to band and release it) really helps them gain a better appreciation for these amazing birds and hopefully supports their conservation. RRP, and in particular Dave Kester, have worked really hard to impact as many young people as possible through classroom visits and station field trips. I really wish this banding station had been active when I was a Luther student!”

Just as exciting as experiencing raptors firsthand is the joy of sharing that experience with others. Biology major Emily Martinson ’22 is a de facto raptor ambassador. “I’ve been able to bring a lot of housemates up,” she says.

After visiting Hawk Hill, one of those housemates, Olsen, became an RRP intern herself. She says, “Sharing the experience and catching birds with other people—especially new people—is always a lot of fun. They’re always just so excited about it—and I am too. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience for a lot of people.”

Learning in community

Having a field research outpost right on campus is a huge boon for Luther students. Interns can pop up to the station between classes and scan the sky for a couple of hours, gaining valuable research experience in the course of an ordinary day. On top of that, the RRP internship is flexible, allowing them to set their own hours and put in as much or as little time as they’re able.

“This internship was a break for me from my busy schedule,” Matzek says. “Being able to hop on a bike and be in the middle of the woods in under five minutes was a great way for me to get outside the classroom and invest myself in what I was learning.” He adds, “This internship is dependent on your personal commitment to it. The more time you put into it, the more benefits you’ll get out of it.”

First-year RRP intern Owen Matzek '25 says, “Being able to hop on a bike and be in the middle of the woods in under five minutes was a great way for me to get outside the classroom and invest myself in what I was learning.”

“It is honestly such a great change of pace,” McTeague says. “It’s easy to get stuck in the monotony of classes and homework, and it’s so great to break up your day by hiking up to the blind and spending a few hours watching and banding hawks.”

It doesn’t hurt that the atmosphere in the blind is welcoming and convivial. A space heater stands at the ready for cold days. There are often snacks within arm’s reach. Friendly graffiti adorns the interior walls. (Anderson-Skelly’s favorite quote? One hawk in the net is better than two in the sky.) But best of all, the interns agree, are the people.

When they aren’t inventing nicknames for each other or drawing red-tails in bikinis, the group might have a friendly debate about what music attracts hawks (Fleetwood Mac, Kester declares, and bluegrass). Or they might enumerate the ways that they’ve tripped, stumbled, stepped on, or otherwise fallen off equipment.

But what unites them is more than snacks, music, and humor. “It’s good to know that we share common interests,” Olsen says. “It’s just so nice to have a community of people that all care about these birds.”

“You don’t really need background knowledge about anything to do with birds to have a good experience up there,” Anderson-Skelly says. “They teach you everything you need to know. It’s very centered around: here’s what we’re doing now, here’s why. We all learn a lot and have a great time up there.”